BC065: A History of Deep House Page

My presentation, in absentia, for Pop Conference 2024

Ron Hardy and friend in the Muzic Box DJ booth; from Deep House Page, via Jacob Arnold

NOTE: This was written to be presented live at USC for the 2024 edition of Pop Conference—last year I went to Brooklyn and presented on kids’ synthesizers and DJ equipment. However, last minute bills and late-coming freelance money (still not here, btw) prevented me from making the trip. In absentia, I read the paper into a recorder, and that was played for the assembled during the panel. It is heartbreaking that I put together this group of people—two of whom, Lily and Zoey, I was (and am) amped to meet in person—and wasn’t able to be there other than through my voice, but it’s better than nothing. In any event, here is the presentation as read.

First put online in 1997, when MP3s were two years old and had almost no real-world traction yet, Deep House Page, or DHP, is a dividing line in house-music historiography. It was the first Web page dedicated to making available DJ sets by the legends of early Chicago house music—Frankie Knuckles, Ron Hardy, Farley Jackmaster Funk, Andre Hatchett, Armando Gallup, and Lil’ Louis among them—as well as from key New York architects such as Larry Levan, Tony Humphries, and Timmy Regisford. In so doing, DHP also codified the core meaning of the term “deep house” itself. It provided a place for old-school house heads to congregate digitally, and also to draft an intimate record of house music’s history. And it inspired future generations of DJs and producers who would make their own tracks and sets in its image. Gone from the Web for nearly a decade now, Deep House Page’s imprint lives on in all kinds of ways; its crucial work as an archive having migrated to numerous other sites and hard drives.

Deep House Page was founded by Gerard Rose, aka Gman; the handful of people I spoken to for this presentation did not know his whereabouts, though I did not do as much diligence as I might have in tracking him down. But his creation, as we’ll see, took on a life of its own, and that is my focus here.

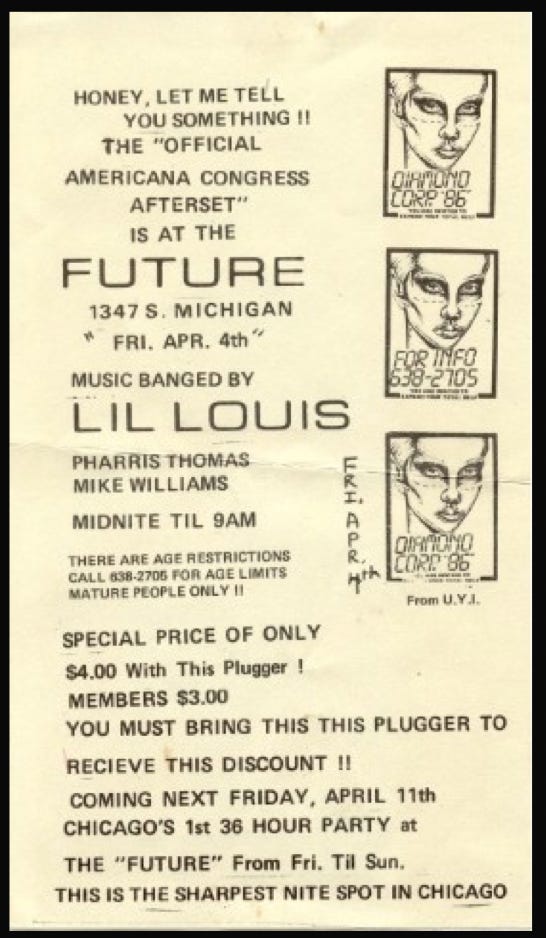

The site’s front page bore all the hallmarks of the pre-blog Internet: a lot of boxes with links in them, enthusiastic not professional design, lots of type. Forums, Mixes, Interviews, History (meaning written pieces), and Rare Flyers all got top-page links, as did New Mixes by DHP Members, Chicago Parties, and New York Parties.

The thing that caught everyone’s attention first was the mixes. “I think the mixes were in RealAudio format,” says Morgan Geist of Storm Queen and Metro Area, who first encountered DHP in 1999. “The quality was brutal and I used to blast them on my headphones and probably damaged my hearing.”

By the mid-2000s, most of the files on DHP were available as mp3, but were uploaded at incredibly low bitrates, such as 36kbps. “He made it as low as possible—where you can hear it, and it sounds OK,” says Manny Cuevas, the Orlando DJ known professionally as M-Traxxx and to contemporary SoundCloud listeners as the proprietor of Manny’z Tapez, itself a major archive, a huge, mouthwatering repository of vintage sets—some 900 of them—culled from a collection of cassettes numbering near 30,000.

Like Geist—and like myself—Cuevas also discovered DHP in 1999, after a younger DJ from Japan with whom he was trading mixtapes told him about it. At the time, like most people, Cuevas didn’t have Internet access. He did, however, have a lot of DJ sets from Chicago that for years he’d been trading with other collectors around the world, thanks to the classified ads in the back of DJ Mag.

Cuevas recalls: “Right when I first saw it, I approached the owner: ‘Hey, I got a couple of tapes of Frankie. Would you like them?’ ‘Yeah, definitely.’ He taped me something in return—he sent me the copy master of the one of Ron Hardy with crowd noise; a copy master of Robert Owens at the Choice; and a couple other ones of Ron Hardy, just as a thank-you; Lil Louis as well.” Cuevas and Gman were not especially close, communicating mainly by email, with a phone call or two: “I remember he was overwhelmed with a lot of people trying to hit him up,” Cuevas recalls.

Deep House Page wasn’t out there by itself. There was a burgeoning, informal community of websites run in the late nineties and early 2000s by and for disco and house fanatics: All Things Deep, Old Skool Anthems, Full Bozeman. Many of their proprietors knew one another and traded tapes. That’s not to mention the mailing lists—conducted through email, but well predating the World Wide Web—where those early webmasters (yes, merely running a website made one a “webmaster” back then) had, in many cases, first connected.

And let me point out for younger listeners: This was the Internet, and these people were making connections online—but they were still trading cassettes. In 1999, music was on the precipice of becoming digitized, but it was only beginning to happen. Digital media hadn’t yet really come of age even though digital communications had.

From the DHP Forums

If clubs like the Warehouse and the Muzic Box had been akin to church, the DHP forums, in turn, were school. I’m especially grateful to the Chicago house historian Jacob Arnold for sending me a dozen DHP Forum threads that he’d saved. (I got a fake malware-attack ad when I tried opening one on Safari, but they were readable as text files.) It’s abundantly clear reading through them that the site’s greatest contribution was as a place for original Chicago house heads, especially, to congregate and share memories and information—to provide details and flesh alike to the tapes, to tell the tales of the clubs from the inside. Over and over, frequent posters like Leonard Remix Rroy and Jamie 3:26 and the one and only Chip E.—whose “Time to Jack” is the record that introduced that word into the house-music lexicon—added one heady memory after another to the public record, it becomes clearer just how close-knit and intense this community is, and it is just as clear how fortunate the rest of us were, and are, to glimpse it even a little.

Among the forum threads Arnold hung onto are a eulogy for Kurt “Jism” Landrum by Chip E., a lengthy interview with Chosen Few member Alan King, and a thread of fond reminiscences of the just-passed Frank Sells, who worked at Imports Etc., the shop that first codified “House Music” as its own selection of music. Leonard Remix Rroy wrote: “You can always tell a DJ who bought music from Frank because . . . they can emulate his voice and manner to a Tee!”

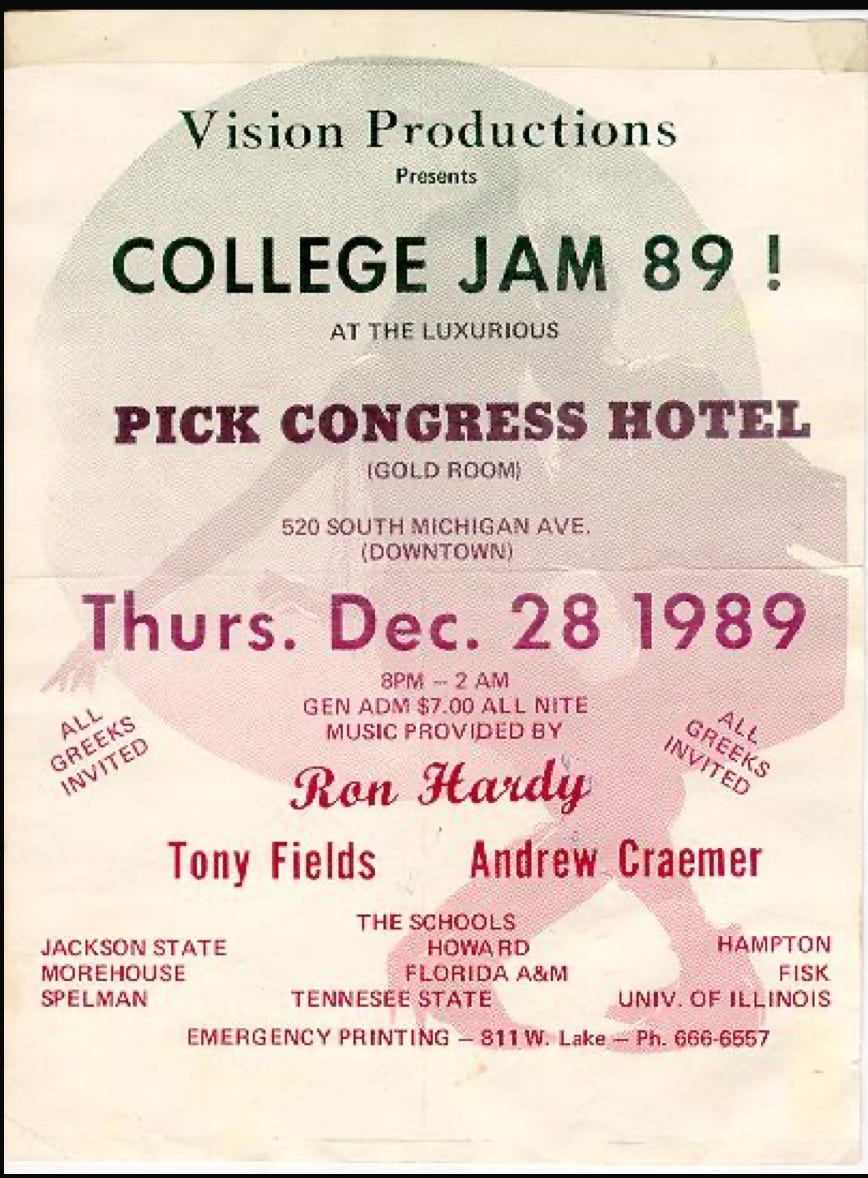

From Deep House Page, via Jacob Arnold

One April 2009 forum discussion unearthed the source of a semi-legendary vocal sample from the tapes: a woman screaming, “My name is Bessie Smith!” On the forum, Jamie 3:26 ID’s it as “A radio station drop for a Bessie Smith play in Chicago . . . back in the 80's.” Chip E chimes in: “My mother was in advertising . . . she wrote and produced the radio spot for a play . . . I had access to her ‘master tapes’ . . . chopped it up, and gave it to Ronnie. On another bit of trivia, my mother wrote the lyrics to ‘Godfather of House.’” A third person recalled the play’s title as Bubblin’ Brown Sugar. And a long, lovingly informed discussion of Farley Jackmaster Funk’s use of that recording ensued.

Ron Hardy’s DJ booth, from DHP

The above-named Jamie 3:26 is also a DJ and house artist. “He was a regular on Deep House Page,” says Arnold. “Some of his mixes were posted there at one point. The 3:26 refers to the address of the Muzic Box. He is really trying to follow in those footsteps [as an artist].” He wasn’t alone. When the Martinez Brothers began learning to DJ as kids in the Bronx, “We’d go to this page called Deep House Page, that had a lot of mixes from back in the day,” Chris Martinez told me in 2013. “They would have track lists at that time so we’d go off on the track lists and find those records, get those records, play them. We really studied hardcore. From 2003 to 2007 was just straight studying—every single day, bro.” The siblings found releases on Discogs, which at that point wasn’t yet a retailer; then they’d go to Dance Tracks or other 12-inch shops and find the records.

The Martinez Brothers also paid close attention to the DJing itself. Steve Martinez told me: “When we heard the mixes, we didn’t try to duplicate the mixes, but we’d always notice the style with which they were doing it: ‘Wow, man, he rode that record [underneath another one] for three minutes.’” Chris again: “We’d just study all that. And this is right before YouTube.” Back to Steve: “Deep House Page was the original. Once we found Deep House Page, we didn’t need anything else.”

Another artist deeply affected by DHP was Morgan Geist. He had long been into radio mixes, including Timmy Regisford’s on WBLS in New York. “Before that I had tapes from WGPR in Detroit—mostly electro/bass/techno—that I loved,” he recently told me in a Facebook DM. But Deep House Page was Geist’s introduction to the Hot Mix Five on WBMX-Chicago. He notes: “I wasn't ever a big soulful house guy. I liked the brutally-looped stuff and futuristic Italo bits. I did an edit of Wham! that aped part of a blend that someone did, maybe Farley or Hurley.”

Aping blends from the DHP mixes would become a frequent exercise among dance producers. In fact, a cottage industry of Ron Hardy-inspired edits came to being in DHP’s wake; according to Arnold, most of these are “counterfeit,” not actually Hardy’s own work. DJ M-Traxxx’s own contribution to this lineage came as a result from his initial trades with DHP founder Gman. “I got one or two tapes of Ronnie with tracks that he never, never released,” Cuevas says. “It was just crazy stuff. And I said, “One day I’m going to be re-edit these or reproduce them.” In late 2021, DJ M-Traxxx released the Tribute 2 Tha Muzic Box EP on the DJ Hell Experience, the German producer-DJ’s custom label. “I redid all the tracks, reproduced them, re-edited them,” Cuevas says. “I put in a heavier kick.”

It isn’t simply the DJs’ edits of well-known tracks that have come to light following DHP posting them, but songs that went entirely unreleased at the time, and not just the DJs’ own. Jacob Arnold discovered DHP around 2005. He was about to move to Chicago from upstate New York, and began listening hard to the Ron Hardy and Frankie Knuckles sets, in particular. He had, he says, “came into house and techno from listening to IDM in the late nineties. It was starting to dry up by [the mid-2000s]. I was looking for other things to listen to.” Arnold had listened to radio mixes in the early nineties from WDKX, in Rochester, New York—a Black-owned station whose call letters stood for Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X—but, he says, “I hadn’t heard anything like classic Knuckles or Hardy sets where they’re playing those edits or those underground tracks from the disco era. It was a whole new canon for me.”

In 2008, Arnold began putting tracklists for sets by Hardy [part one, part two], Knuckles, and Farley Jackmaster Funk [part one, part two] on his website, Gridface, and the mixes themselves on Gridface’s Mixcloud page (all are still up). He began filling in blanks thanks, in part, to DHP forum regulars who began adding comments and sending in titles. “Just by nature of me bringing attention to those, some of the original producers went back in the archives and found some of those tapes they’d given Ron Hardy, like Marshall Jefferson—he released a remake of one of them,” says Arnold. “And Craig Loftis, after I spoke with him, there was one of the tracks that he put out on Loftis Classics as a twelve-inch. That was in a Ron Hardy mix that nobody could identify at the time. Then talking to Vince Lawrence about that edit he did of ‘Sensation’ with Ron Hardy—all these things were really unidentified at that point. It really helped us track down some of these legendary things, where people had nicknames for them.”

Deep House Page was still up and running at least as of 2014—I said so in the long draft of the book I was writing then, which was published a year later. According to Arnold, DHP was shut down suddenly: “It was something where the host for the forums actually just pulled it with no warning, is my understanding. Some members of the forums tried to revive [it as a] Facebook page or group, [which] wasn’t really successful.” But Deep House Page planted many seeds—in a way, it’s become as much a foundation stone as the tapes and tales it once, if you’ll pardon the term, housed.