BC075 – Five Mixes: Simon Reynolds (May 2024)

A Q&A with electronic music’s foremost chronicler and the author of the new 'Futuromania'

My next guest needs no introduction. If you’re reading me, chances are you’ve been reading him just as long or longer. Nobody has written more vividly or concisely about dance music than Simon Reynolds and it is not likely anybody ever will. A sweetheart, too, as you’ll read. We’ve spoken in public together when he did the Q&A with me in Los Angeles for TUIM. Naturally, I elected to build my questions for him—about his career, his time as a raving junglist, and his new book, Futuromania—around five sets (three radio shows, two CDs) of my choosing, a prompt that opened up some welcome avenues of thought on my end. Simon, as always, had lively things to say about everything.

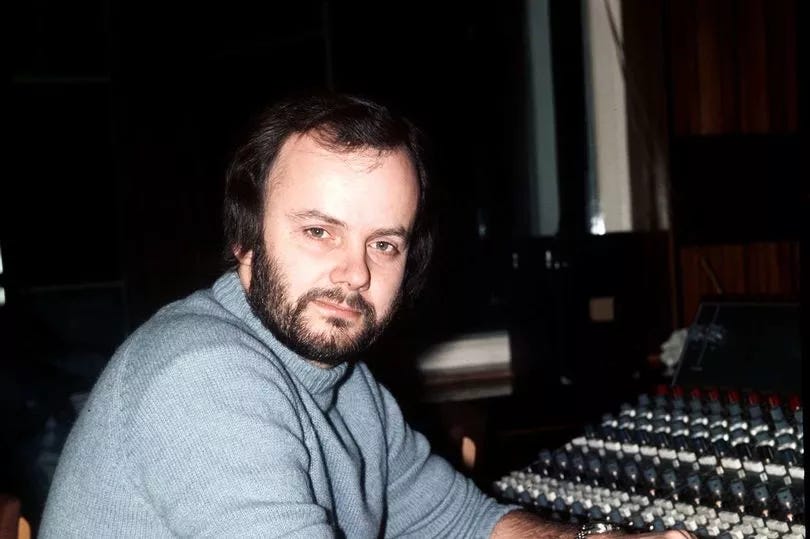

Photo by Joy Press

You can hear four of these sets on this YouTube playlist.

John Peel, Punk Special (BBC Radio 1, December 10, 1976)

MM: Were you listening to John Peel by the time this episode aired?

SR: No, I don't think I was even listening to the radio at all. That’s December ’76, right? I would have been thirteen. I think I was really into science fiction at that point. Music kind of dipped away for a little bit at that period. I think I started listening to the radio a year later. I was liking ELO. So no, I didn't know who John Peel was. I wouldn't have known that punk was happening at all.

When did punk enter your house?

I think it was some point in early ’78. I remember reading about it in—my parents got the Sunday papers. We had this thing in England, the Quality Sunday—it’s been like the New York Times Magazine, we call them color supplements. The Observer has one, The Sunday Times has one, The Telegraph has one. I remember reading—there was a several-page spread, largely photographs of punks. I was like, “Oh, that's kind of weird.”

The Goodies [BBC; 1970-79] was a very popular comedy show by people who were associates of Monty Python early [on]—before Monty Python. They did their own version of the same, oriented towards kids, I suppose. They did an actually very funny spoof on punk. [“Punky Business” episode, November 1977.] The whole episode was a spoof on punk. So, I knew something's going on, but I wasn't listening to it.

Then my brother brought home a tape that had Sex Pistols stuff on it, and a live concert from BBC Radio by Ian Dury and the Blockheads. Then he started bringing the Ian Dury album, X-Ray Spex singles and Buzzcocks singles. Never Mind the Bollocks was really the album that we all were astounded by and thrilled by. The destruction was a big part of it: “I want to destroy!” I was fifteen and, I think, pretty puerile individual. And we weren’t really into vandalism, but that kind of adolescent mayhem was where a lot of our energy went. So that assault was the initial bit; the swearing, the foul language.

Ian Dury had a lot of foul language as well, which initially grabbed me. Then you listen to Ian Dury and read the lyrics—they’re really great writing: poetry, or very funny comic verse, as well as shocking. And the music's really good. I wouldn't have been able to say I realized it was funky, bluesy music rooted in decades of Black music. But in a funny sort of way, Ian Dury introduced me to a lot of that stuff.

To the Black music, or to the punk, or to both?

Both.

When did you start listening to John Peel?

It would have been probably ’79. I was drawn in by New Wave, I guess—all kinds of odd groups. Punishment of Luxury was a group I really liked; PiL; I was grabbed by the Fall, Joy Division. And also, because of Johnny Rotten, I followed this sort of logic through: What did the interesting people in the Sex Pistols do next? Well, the two interesting people, for my money, were Johnny Rotten and Malcolm McLaren, and I just followed what they did almost religiously. If you listened to PiL, you probably started listening to John Peel as well.

I was also thinking about how Peel helped set the agenda for what would become post-punk, particularly in terms of its omnivorousness.

Yeah. It was a bit annoying because—there are a few, but there aren't nearly as many Peel shows that have been preserved from before punk. But if you listen, they're very, very eclectic. He's playing reggae. I'm not sure if he's yet playing African music, but he's playing a Cajun record. He’ll play quite old things, the roots of rock and roll, but then he’ll play the whole of Tubular Bells, or Robert Wyatt, or have Ivor Cutler come in and do a session. What's his name? The guy who was in Bonzo Dog Band? Vivian Stanshall did these sessions that were essentially comedy soundscapes. He played a lot of folk rock. Even during punk, he was still doing sessions with June Tabor and the royalty of British traditional music—

—which Rotten also liked—

—so it was very, very eclectic. And, I mean, I would appreciate it more now. At the time, I would be waiting for, you know, the next Fall record to play. His theme music, which he never got rid of, was this track by a group called Grinderswitch, which is like this boogie shuffle . . .

[Note: This is the one Simon means, not the one I erroneously attribute as follows.]

That’s “You’ll Never Walk Alone.”

Oh, is it? Right. Yeah. That was always somewhat puzzling, that he would play quite a lot of these sort of older records, bluesy sort of things.

I think that in particular is a Liverpool FC song. I think that's the reason he played it for his theme—he was a football fan.

Yeah, I mean, he clearly liked a lot this music that punk disdained or tried to get rid of. And it crept back in, I think, here and there. I think what's interesting about that show is that it’s the beginning of this tremendous—I don’t wanna say “rebranding,” because that's such a non-“Peel” sort of word . . .

I think it fits, though.

Yeah. He basically sees which way the wind is going and he jumps very enthusiastically on it. He gets into this whole thing of wanting to play very roughly made DIY records from small towns all around the UK and around the world, in fact—kind of a regionalism thing: “The regions and the provinces will have had their moment.” Because it's BBC Radio out of London, it goes to the whole of the Great Britain and reaches into Ireland and probably bits of Europe as well. It's sort of decentralized, yet the centralizing power of the BBC sends it out to small towns like my own small town.

I was listening to that Peel thing, though, and I think I did feel like a lot of the excitement you have to mentally historically reconstruct. [chuckles indulgently] Quite a lot of it sounded fairly scrappy. It was literally at that precise moment.

Because nothing sounded like that. You weren't allowed to sound like that.

One thing I got out of doing this glam book that I was surprising to me was—I took it as my opportunity to read the music papers on that era from about 1970 onwards: Melody Maker, NME, and other ones. And one thing that strikes me is that the word “punk” was in pretty common critical parlance from 1972 onwards in the UK. I think they were picking it was because people were picking up on what Lester Bangs and people were already talking about in Creem and other similar American publications.

There's a famous press conference with Bowie, where one of the guys at the NME asked, “What do you think of these three buzzwords?” And it was “punk,” “funk,” and “camp.” What really surprised me was people would review Suzi Quatro records or records by the Sweet and use the word punk to discuss it. It was . . . kind of rehearsed for: You had the excitement of the New York Dolls, the summer the Stooges—vaguely punky things rehearsed for quite a long time before it actually finally happened.

I like to do these rock counterfactuals. I've not written them up. I like to do in my head or on a notepad. One of them is trying to imagine a world where what would have had to happen for the New York Dolls to happen—like, when they happened, they were kind of a bust, really. They had all this critical support . . . What if they'd been if a punk-level convulsion—if they'd been the Sex Pistols? Because many of the elements are there. I think they don't quite have the tunes that the Pistols had. But also, I don't think they're quite as serious, in a weird way. It's this deadly seriousness of Rotten, where you really think, when he says, “I want to destroy,” he means it.

Ezy D, Don FM, Xmas 1992

MM: Obviously, I chose this because it’s on your YouTube page. Paint us a picture of what you’re doing on Christmas of 1992 besides taping this mix off the radio.

SR: I would have been back in England. I got married in August of ‘92. Prior to that, as part of getting married [to Joy Press, an American], you had to be in the country for certain amount of time, and then you had to stay in the country after [for a certain amount as well]. So, a big chunk of ’92, I’m not in the UK. As much as I loved being newly married and all that, I was glad to go back to England because there was all this excitement going on there. I did have a very active period of going to clubs. I think I went to a Spiral Tribe rave that was in an abandoned Inland Revenue, like IRS, Tax Day depot, abandoned in the north of London, in the dead of winter. It was horrible. It was cold.

That’s so symbolic.

There was no bathroom. There was a designated pissing room—there was just a wooden board and it just lay there—and they were playing really horrible music. It’s something I can laugh about now. But at the time, it was grim. The music got very hard and punishing. And I think people were in a bad way drugs-wise, as well. The wonderful midsummer vibe of Spiral Tribe’s legendary rave wasn’t there.

But yeah, I was taping madly. I knew I was going back to America and I needed my supply. I taped, I don’t know, forty hours or whatever of this music. I shared a house of this guy, and he had a really nice stereo in the living room with a good radio. I would even leave the tape on when I went to bed, leave it running just to get a bit more, so I had all these quite high-quality tapes. But what annoys me now is that I was still taping over advance things I’d been sent, or recording things on cheapo tapes. I was like, “Why in fuck should I record these things on metal tape?” I didn’t realize that it was [going to have] historical interest, that I would be playing it for years to come.

Did you actually play back all forty hours of tape?

Yeah. Most of this stuff was [airing] at the weekend—then I’d play it during the week while I was writing, doing my work. So, I already knew these things pretty well before I went back to America. And then in America, I just played them over and over again.

At the time, I was working on The Sex Revolts [Reynolds’ and Press’ co-written book from 1995]. It was getting to this point where the money had run out and we were desperately trying to finish it. Joy had a staff job at a publisher. I’d drink loads of coffee all day and play these tapes to rev me up. Joy would come home in the evening and hear the mad jabbering voices, and I’d be there almost palpitating with caffeine, trying to get the first draft of The Sex Revolts done, so that we could then remix it together.

I associate pirate tapes with working on The Sex Revolts, being in New York, and just rushing off this music. It became deeply ingrained—if you play the original track [from] a lot of these tapes, I can supply the emceeing that would be on the tape. If you, say, played “Lost Entity” by DJ Trace—I’m not gonna do it for you, but I could perform MC OC, word for word, his emceeing over it, the timing, everything.

Were you only listening to your own tapes of jungle pirates or did you trade with others?

Some friends would send me things sporadically, but not really. What would happen would be—I think in ’93, I was back a total of two and a half, three months. It was early January, the next time was August; I think there was time in the fall, as well. When I was there, I would just go crazy taping stuff. Each time, the music had jumped ahead hugely. By early ’93, it was fairly definitively dark. And then towards the end of the year: “Oh, the musical, ambient-y, soul elements are coming through. This is so interesting. I wasn’t expecting this.”

One thing that impressed me while writing my Wire Primer on pirate sets is just how quickly UK hardcore, or breakbeat hardcore, the stuff that becomes jungle, becomes itself. There are gradually some of the ingredients floating individually around, but when they combine, they assume their true shape really quickly—like a brush fire. Is that how it felt at the time?

Yeah. In ’92, there’s a lot of tracks have fast breaks, and the bassline is fast. I call it a bippity bass. It sounds like the heart rate of dancers on E. But then, at some point during that year, this thing is discovered, that you can have a slower bassline. Sometimes it’s a reggae style [bassline]. Sometimes it’s a sort of oozy 808 thudding sort of bassline—I always think of that track “Lords of the Null Lines” [by Hyper-On Experience, 1993] It’s an 808 bass—a dark kick drum that’s so distorted and detuned—it’s sort of reggae-ish in feel, but it’s sort of something else.

There’s a lot of Reese bass as well.

Oh, yeah, that’s another flavor that was sort of brought back. So, once that’s discovered, it seems to open up the music. . . . It’s still frantic, but there’s also a kind of sensuality that emerges: this really gripping thing of the chillness and the frenzy at the same time. I’ll never recover from the excitement of that, I suppose, in some ways.

DJ DB, History of Our World Part 1: Breakbeat & Jungle Ultramix (Sm:)e CD, rel. June 28, 1994)

MM: The DJ DB mix is important for me personally—I loved jungle, heard it at parties, and while I know there are more exciting sets out there in terms of the actual deejaying, it works so well as a history lesson. It’s a well-designed compilation of the kind that the CD era had in abundance thanks to labels like Rhino, with the added kick of being mixed by a real DJ and not just ProTools. And you wrote the liner notes. How did you get that gig?

SR: I think I got to know DB through going to his club NASA a few times, or going to the shop [Breakbeat Science, which DB ran] and meeting him there. I wrote—I wouldn’t say “the same story” many times. But I wrote about jungle as many places as I could; one of the very first places was actually Vibe. I guess I was the person you’d go to if you wanted a journalist to write about that music at that time, and we got pretty friendly over the years. DB is generally one of my favorite DJs. I’m a bit skeptical about the mystique of DJs because many of my best nights have been with the less-known DJs. And he was well respected, but he’s not Jeff Mills level. The probably the best dancing nights of my life have been with DB or probably equivalents in the UK.

You’re not wrong. That’s true for any DJ aficionado: a good DJ is a good DJ. I’ve heard loads of great sets by total nobodies. It’s just that you can’t sell pieces about total nobodies.

Absolutely. I’ve seen amazing DJ sets where the artistry of the DJ is paramount, like, say, LTJ Bukem. But as a result of his artistry, the individuality of the tracks is lost. Part of Looking Good, the label, was, “I want loads of music that’s very like my own music so I can do these amazing seamless mix-scapes.” I think the same with Jeff Mills: The reason he played all these basically unfinished tracks is because they are good to do the amazing DJing with. Whereas I think DB had a very good balance of the anthem, and the deeper track. It’s all these great tunes, all these hands-in-the-air tunes, and then, on that particular mix, he goes for some of the more unusual, stripped-down mixes of certain tracks. He’s hands-down one of my favorite DJs. I have never seen him do a bad set, never not had a great time. And he was the champion of this music that I loved, trying to build it up in America. So yeah, respect to DB.

What would you say the differences were between the UK raves and NASA?

I wasn’t doing a survey, but I got the impression it was a lot more middle class and upper middle-class thing in America. In that period, there was a much stronger fashion element in America, in New York—kids in crazy-wide pants, and a younger crowd. It was actually a whiter crowd as well. If I were going to see the music that’s on History of Our World in London, it would be probably at a club like Labyrinth, where the audience was 50-50 white and black, and more working class. I mean, quite a few sharp-looking people; there’s a lot of people who also look like ravers, but in a fairly nondescript way—baggy clothes, but not the crazy fashion statements that you’ve got on the New York scene.

The other thing that I noticed was, the crowd in UK dance as one, like a mass. Either they’d be facing where the DJ was, or they wouldn’t be able to see the DJ, but they’d just be dancing as a mass together. But in in America, I noticed quite early this thing of like, a people falling a circle around a really good dancer—[with] the liquid moves and involuted stuff, or a sort of semi-breakdancing.

Popping and locking.

So that was interesting that there was this sort of spectacular realization of the dancing or performance thing. Whereas there wasn’t really that [in the UK]. I mean, you had professional rave dancers at some clubs, whose job was to stand on a podium, right? You’d see exceptionally good dancers, usually a girl that was just a really good dancer. Whereas this [in the U.S.] was . . . a competitive thing, really.

At one point during the nineties, did you have “junglist” on your passport? Or is that a myth?

It’s a joke. It’s more me trying to say I was so patriotic for the music. “Junglist” actually does sound not far from my actual occupation. Journalists, junglists, they’re quite similar. At the time, I was very fanatically [saying], “This is the greatest music and everyone should be into it. Why aren’t you into it?” That was my pitch. I was checking out all the other things at the time, buying loads of records. Whenever some new fuss was made about something, I’d go out and at least listen to it in the record store or buy it. But it did seem to me the cutting edge. And everything about it—musically, but everything about it, the cultural ramifications of it and politics of it—seemed super compelling and the opposite of Britpop, as well. It was the real Britpop—this was the real British stuff you should be excited about.

Tuff Jam, Underground Frequencies Volume One (Satellite CD, rel. July 5, 1997)

MM: When we began preparing for this interview, you mentioned you’d need to acquaint yourself with this set—a formative UK garage mix CD—which is funny, because I’d chosen it because it was in the discography of Energy Flash.

SR: I realized as soon as I pulled it up, I saw the sleeve: “Of course I’ve got this.” I was in America full time then, and it was very hard to get hold of speed garage. Just a few tracks were coming through in the record store. But the jungle people were not interested at all. And New York house people were like, “What is this? This is rubbish.” I’d grab anything. I think I probably bought everything of speed garage that reached America—there weren’t many. And then there was one [section of the discography] where we have all the comps that existed—there only three, but that was one of the best. There’s actually five or six, then, the following year. There were tons of them.

But yeah, that was really good. I think what’s interesting about it is it catches [UK garage at] a very nascent point—a big chunk of it is just American garage music, isn’t it? And then there’s the stuff that is British, but it’s very, very primitive and very good, but it’s trying to be classy and soulful and polished. Smoking Beats’ “Dreams” is such a gorgeous song. Mutiny, “Bliss”—I’d completely forgotten about that track. It’s gorgeous.

And then you have you have Todd Edwards and the Armand Van Helden stuff. Those are the Americans who are the most close to what’s going to happen [in the UK]. What’s emerging out of UK is helping to catalyze it, but they’re also going to be carried along by it, in a way. And you only have a little really tiny bit of actual speed garage on it. The Double 99 tracks—not sure what else there is. But it’s a great comp. It captures this sort of formative motion.

I imagine—and this would be true for a lot of people at the time—that it probably wouldn’t have slotted in your mind as a DJ mix, but as a compilation.

Yeah. I was trying to convince people—friends and employers, I suppose—that this was happening thing and we should write about it. At that point, I was just about to be at Spin. I remember giving some of my colleagues a tape, and included things from this mix CD that I had to fade, to try and turn them into tracks. I suppose that confused the listeners. I remember the response was, “It’s just house music, isn’t it?” I couldn’t quite explain to them that it was significant.

It was R&B, is what it was. It was the early glimmerings of Timbaland and the like happening over there simultaneously. And that’s a product of, and part of, the change in production style, where people are working with computers and are able to move things around in minute ways.

Yeah, it was. It took me a while, [but] I really enjoyed it. But I was not convinced it was gonna be as big a revolution as jungle, because it was so grounded in house music. But then I think when the two-step element came through, I was like, “Oh, yeah, this really is rich in so many possibilities.”

I remember [the critic] Jess Harvell saying it was his favorite music to dance to, speed garage. And I was like, “Oh, actually, it is the perfect music to dance to, isn’t it? It’s just the right tempo. You don’t have to be alter your neurology or biochemistry to keep up with it. It has all these sort of jungly elements in it—not so much on this CD but later on, more and more of a jungly input that comes in, sexy and sensual, the right BPM, but there’s all these little syncopations. It is glorious music to dance to, I think.

It’s interesting to me that if you think about Disclosure blowing up, and then more recently Pink Pantheress and people like that, you could you actually say that garage beat jungle to the U.S. crossover.

Yeah. Disclosure were really big here. It does seem to have, in a weird way, a longer pop life. But I was convinced 2-step was gonna cross over. I was disappointed that it wasn’t—like, Craig David had a hit here. And then what’s that other guy? Daniel something?

Daniel Bedingfield.

But you know, I thought then it was gonna bust through. But it didn’t.

I think in America, they were just seen as British r&b, doing what Timbaland was doing, which is not an unfair assumption to make, but it didn’t translate as a culture. And it didn’t translate as dance music, per se.

Before speed garage, I had very little interest in garage. And in fact, it helped me get into the history of garage and appreciate people I didn’t know, like Mood II Swing and Masters at Work, more than I had. I liked the odd thing; I really liked [Hardrive’s] “Deep Inside,” [a MAW track]; I liked [Jaydee’s] “Plastic Dreams.” But my focus was largely on the jungle thing. Before speed garage, I was dimly aware that there was this relationship between jungle and garage, because there was this second-room thing. Like, if you went to a techno night or a trance night, the second room would be chill-out music, ambient or whatever. But the second room of jungle was always warm, soulful house music and garage, basically. And it puzzled me a bit, but now I can see that it makes total sense—polished, and it had this sort of untouchable elegance about it that would appeal to junglists when they wanted to relax.

Rustie, Essential Mix (BBC Radio 1, April 7, 2012)

MM: Obviously, I picked this because you write about him in the book—Glass Swords the subject of your treatise about “digital maximalism,” so a two-hour set highlighting a 42-minute album seemed even more digitially maximal. Based on this selection, is it safe to say that, in the main, you’re generally more favorable to maximalism than to minimalism?

SR: Oh, right! My response to this mix was that I felt like at the end of the day, as much as I enjoyed putting on the maximalist hat in that piece, I’m probably more minimalist. [both laugh] I There’s a strain of rave music that is maximalist that I really like—like this group Hyper-On Experience, or Acen. The tracks are just fizzing with elements, and they go through these changes. It’s not like one idea, repeating over and over. It’s not like a Basic Channel record or a Maurizio record, which I love—tiny little flickers of changes, essentially, on one long loop. That’s a lot of [UK] hardcore—there’s this [sampled] phrase, “Get busy,” which the people [making it] used, and it was busy . . .

It was teeming.

Yeah, teeming with stuff, chopped and changed. But I listened to the Rustie thing; there’s lots of great things in it. But I felt kind of exhausted by the end. I felt like I was overstimulated. I had that sort of frazzled feeling—a day-of-being-on-the-internet sort of feeling, which is every day for me. That feeling of where you’ve tried to do your work, but also listen to music, and also check your socials—all these things—and at the end you’re just completely burnt and fried out.

It’s a bombardment.

Yeah. But there were some great tunes in there. I was actually a bit surprised. I was like, “One of them is amazing. What is it?” And then it turned out to be Baauer, “Harlem Shake.”

There’s another reason I picked this—two, actually, that intertwine. This set hit came along right as EDM blew up in the States, and that was another kind of maximalism. But also, Rustie’s mix contained the world premiere of Baauer’s “Harlem Shake.” One year later, owing completely to a fluke of chart-gathering rule changes at Billboard, that track became number one in the U.S. for a month, one of the biggest pop hits of the EDM era. You obviously cover that end of things a bit more in a new foreword to a mid-2010s re-publication of Energy Flash. But where do you hear digital maximalism, per se, having gone in more recent years?

I don’t know, really. I think, as you say, a lot of EDM is essentially the same thing as Skrillex. I suppose a lot of pop music really is kind of digital maximalist insofar as it’s very digital sounding and dramatic sounding and epic sounding. What do you think? Do you think Rustie had a kind of legacy?

That’s hard. I don’t listen to a lot of music these days that is from these days, except when people play it in sets. I do listen to DJ sets, mostly. I’m thinking here of the Kendrick and Drake tracks, the battle tracks. I haven’t really listened to the Drake tracks, because who cares? [Simon laughs] But the Kendrick tracks—increasingly, it feels like the music in the big songs I hear is bed music for the singer or rapper or vocalist to display their persona. I feel like that big EDM sound of ten years ago has become like a pad or a preset. Robert Fink wrote about Orch5, which the orchestral “hit” of “Planet Rock” comes from. It’s like digital maximalism is now one of those now—a note you hit and it all blares out. It reminds you of that largeness, but it’s discrete. It’s not itself large.

I suppose one thing that is [an] extension of it—I don’t know if it was happening; there were the earliest hints of it happening when I wrote that piece, and I just missed it and forgot to include it, but it was might have been a little bit later—is PC Music and that whole hyperpop thing. That sort of super [artificial]—there’s nothing organic in the soundscape.

It’s squeaky.

Harking back to trance and synthpop and every sort of strain of very artificial-sounding, this-is-the-future [style]. It’s bright and shadowless, I think is the word I used in the piece; cartoony, as well.

Absolutely.

And I never really got into the PC Music thing. But I like SOPHIE. I mean, SOPHIE’s amazing.

I only learned to like SOPHIE after the fact.

Yeah.

But you’re exactly right. For many of the young DJs I’m friends with, ground zero for them is hyperpop. There are hyperpop DJ nights. A lot of people into that are in their twenties and have begun DJing within the last five years.

Some of the stuff that Kieran [Simon and Joy’s son Kieran Press-Reynolds, himself a music journalist] is into, the sort of online genres, are like digital maximalism. But it’s also sort of lo-fi, as well. It’s very distorted, gnarly sounds and very, very extreme use of Auto-tune. But it’s also for attention deficit disorder, sensorium, a neurology that needs something, a musical event, to happen every few bars.

Whereas, one of the things I liked in recent music, and it’s in the book, is trap. I make this point in the [book’s] piece on ambient: I talk about trap again, Auto-tune trap. I say it’s like one of the last bastions of minimalism on the radio. You hear these rap tracks where it’s just like the beat is just a sort of spangly loop, going round and round, like some of the Playboi Carti things, or Lil Uzi Vert. It’s like this almost IDM-like, Aphex Twin-like loop, spangling along. It doesn’t really change much. And the vocal is quite repetitive as well—doing this half-rapping, half-singing thing. The lyrics are sort of about the usual stuff, but they’re kind of irrelevant; it’s more about the voice texture. So that’s something where it’s very glossy sounding, but it’s also—not maximal, because it’s quite repetitive, enough to slip into the background.

I find it fascinating how Aphex Twin hasn’t gone anywhere. You ask almost any musician working in any kind of electronic realm, and they will mention him as an influence. He’s almost as universal as Daft Punk.

I teach music students—I have a mix of students, but most of them are from the music school. And a lot of them are in awe of SOPHIE’s sound design. It does seem like sounds you never heard before. Although that sort of the general glossiness and artificiality does sort of remind you of earlier trance and eighties synth music, in a way. I think SOPHIE would be the great inheritor or extension of that sort of stuff I was talking about.

I think of Futuromania as being your L.A. book. Most of it dates from after you moved there. And in it, you engage pop music more directly than usual—in part because pop and indie have themselves become largely electronic over the past 20 years—and partly because you have spoken of hearing things such as classic rock anthems in new ways from living in cars more. How much Los Angeles is in this book to you?

I never thought of that. But actually, it’s very true. I really never listened to the radio in New York. I had a phase I listened to Hot 97 FM, because they had a dancehall show, and I was having a phase where I was obsessed with dancehall, and they had a really good show done by that guy who used to make New York house records for Nu Groove.

Bobby Konders.

One of the great career reinventions anyone’s ever had. But yeah, I really never listened to the radio. It doesn’t seem to fit New York. But as soon as we moved to L.A., we had a car. I rediscovered the wonder of radio, which had been a big part of being a teenager, and then the pirate radio thing. This was like, “I love radio.” There’s so many—like the pop stations, local commercial rap stations. If anything, I wasn’t that keen on NPR . . . you know . . .

Like Morning Becomes Eclectic?

Yeah—a little too polite. Some interesting things, then I really want to hear either classic rock or something in the Top 40, or a rapper. The kids wanted to listen to that kind of thing, too. So I sort of fell in love with radio and listened to a lot of pop music. And it happened to be, as you say, at this time when a lot of ravey ideas were having a second life. There’s this track I love by Dev, “In the Dark.” It’s essentially a UK garage track, more or less, but it was a really big radio song here.

I’ve realized, after a bit, that there were these records that were huge in L.A. or maybe the West Coast generally—probably Southern California—but then, at the end of the year, the critics polls, they weren’t visible. That’s because most of the critics are on the East Coast. There’s this track, Sage the Gemini, “Gas Pedal.” On the rap radio station, it was on once an hour. It was my favorite track of the year. I looked at the critics’ polls and even rap specialist polls of the year, and it was nowhere in sight. It was just a pure [local hit]. So that regionalism, again, is interesting. There’s these things that pop off somewhere in America, but not everywhere. It’s fascinating. That’s a big part of American music history, isn’t it, the regional smash?

Absolutely. Two more questions, one short, one long. Short one first: Whose idea was Futuromania? Yours, an agent’s, an editor’s?

It’s got a bit of a boring, convoluted publishing history. Initially, a guy I’m friendly with, Valerio Mattioli, wanted to do a collection of the hardcore continuum writing in Italy. I was into the idea. I thought, I’d better check with my main Italian publisher, what they think of this. And they were like, “We’d rather you didn’t do this, but why don’t we do . . . ?” Between the two of us, we came up with the idea of a book that included the hardcore continuum and writing and then a lot of other stuff, you know, and so I did this book in Italy feature me had actually quite a lot of avant-garde music—that’s one of my passions, musique concrete and weird voice stuff, but from the academy, really . . .

Lab-coat electronica?

Yeah, exactly. And then, once I’ve done that, I thought . . . there was a period when I didn’t have an agent. My other agent retired, and [it took a while to] find a new one. I actually have quite close relationships with my publisher in Germany, so I pitched it to them and they did it, but they wanted it slightly different. It ended up being more like—in Germany, Energy Flash was never translated, because I feel they have their own great German writers writing in German about that music, so there was never a space that needed to be filled by it. So, I used some bits of Energy Flash; I made it more like my electronic dance-music book. Then I hooked up with my publisher, Lee Brackstone, whom I’ve been with at Faber, and he’s got this new thing, White Rabbit. He was keen to put it out, but wanted it to lose the avant-garde stuff and make it just more about popular music or youth subcultures.

So, it’s sort of my idea that kind of prodded by and reshaped by other people, I suppose. I liked the idea of having a book that . . . I can’t have it overlap with too much with Energy Flash or Rip It Up, which has stuff—or Bring the Noise, which has a lot of hip-hop stuff. So it’s oddly composed out of the need to avoid overlapping with those things, but to also cover some of the same things.

Well, it’s coherent.

Quite late in the process of doing this English version of it—I had more genre-based pieces than I thought, but I became actually more interested in the human side of it. I’d had some piece about darkside [jungle] for Artforum that was called “Machine Gone Mad.” It was very the height of reading Deleuze and Guattari and Virilio. And it was about the subconscious of the machine, eating up its human components, people [taking] drugs to keep up with the machine. It was this thing—an academic wrote a piece about it—the anti-humanist tone, which is this tone that enters academic writing and theory, where you’re continually depersonalizing everything. That was very interesting. At that time, it was very exciting.

But now, as I’m older, it’s actually affected by people I know dying, musicians and just people. I’ve become much more interested in the human stories. And the fact that it is these oddball individuals. So instead “Machine Gone Mad,” I thought, “No, I have a piece on Rob Haigh” [of Omni Trio]. I spoke to Rob Haigh at length. He’s a lovely guy. He’s got a very strange story. He started out as a glam rocker; he was in a band. He was inspired by Bowie. Then he went postpunk, he made these piano records. The bit where he coincides with history, in the sense that he’s a key figure in jungle—in that, you know, as that great track on History of Our World, that DB mixes so brilliantly with the Nookie/Cloud 9 track. I said, why not have it on this exceptional and oddball individual, and have his whole journey, even though it only the middle of it really coincides with electronic music?

I had a general piece of footwork, but I thought, “Oh no. I’ll use the Jlin piece because that’s a person.” She’s quite an interesting, tenacious character, and she talks about her music in those terms of her struggle to create something out of nothing. I think it’s doing the books like Rip It Up and the glam book, but there are so many strange people, and they kind of somehow find themselves in the right place at the right time. And they’re often flawed individuals as well.

This is your first book in eight years. We haven’t discussed this before, but I found the last one you published, Shock and Awe, your history of glam rock, quite affecting. It was clearly a very personal piece of work for you, particularly the detail with which you recall everyday British life in the early seventies. You’re not a character in it, but we can feel your presence strongly in the narrative. I get less of a sense of that with Rip It Up and Start Again, which isn’t a criticism—it feels like you made a decision there to stay closer to what your research brought you.

If that’s kind of funny, because the sense of memories I have of that time are quite small. I was just a kid. It’s like quite hazy memories of seeing things on TV. With Rip It Up I have a lot more sense memories. I mean, compared to the number of shows I went through as a music journalist, I went to a really small number [as a teenager], but I went to quite a few bands. I saw the Fall and Echo & the Bunnymen; even Haircutt 100 I saw play live. I saw the Slits, I saw Killing Joke, Adam & the Ants, Bow Wow Wow. I think I’m just easing towards putting myself more in things. There’s a bit of that in Energy Flash.

I don’t think it was a conscious decision. But I think the thing is the people I was interviewing were so interesting, that they had to be the foreground really, and just dominate the spotlight. It makes sense that I’m just like the host of the party. I’m convening these voices, and squeezing in my memories. I did have some memories I could have drawn on, but all the time, I was listening to the records or reading about it in the music press. I wasn’t gonna shove that in.

Whereas glam feels like it’s happening to you.

I don’t know. I’m glad you take it that away. I mean, it was a personal book insofar that I love this music, but a lot of it was actually attempting to reconstruct it to research and to make up for the fact that it wasn’t there. That’s why the music papers are are so great, because they had all so many facts and details, like what the cost of joining a fan club was. I don’t know if I even used it, but what a gig cost—great stuff to do with kind of behavior at Slate concerts and stuff. So, I just tried to put as many concrete physical things as I could, even though I was a small child for most of it.

What’s on the horizon? Is there another book?

I’m doing a new book. I actually will have this thing you’re talking about, with me in the text more. It’s about the late 80s-early 90s underground rock underground going overground. It’s the stuff that music papers covered. I can’t really avoid having me in it because I knew all these bands, I interviewed many of them several times, I went to concerts endlessly. Some of the bands I was friendly with. I can’t really leave myself out of the narrative, but I’m going to try and make that a virtue in some way. And it’ll be fun. It’ll be personal. It’s about the music press, I think, as well as about the music. It’ll have an elegiac quality.