BC083 - Q&A: Tricia Romano (May 2024)

The author of 'The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of the Village Voice' discusses formative DJs and spinning at the Tribeca Grand

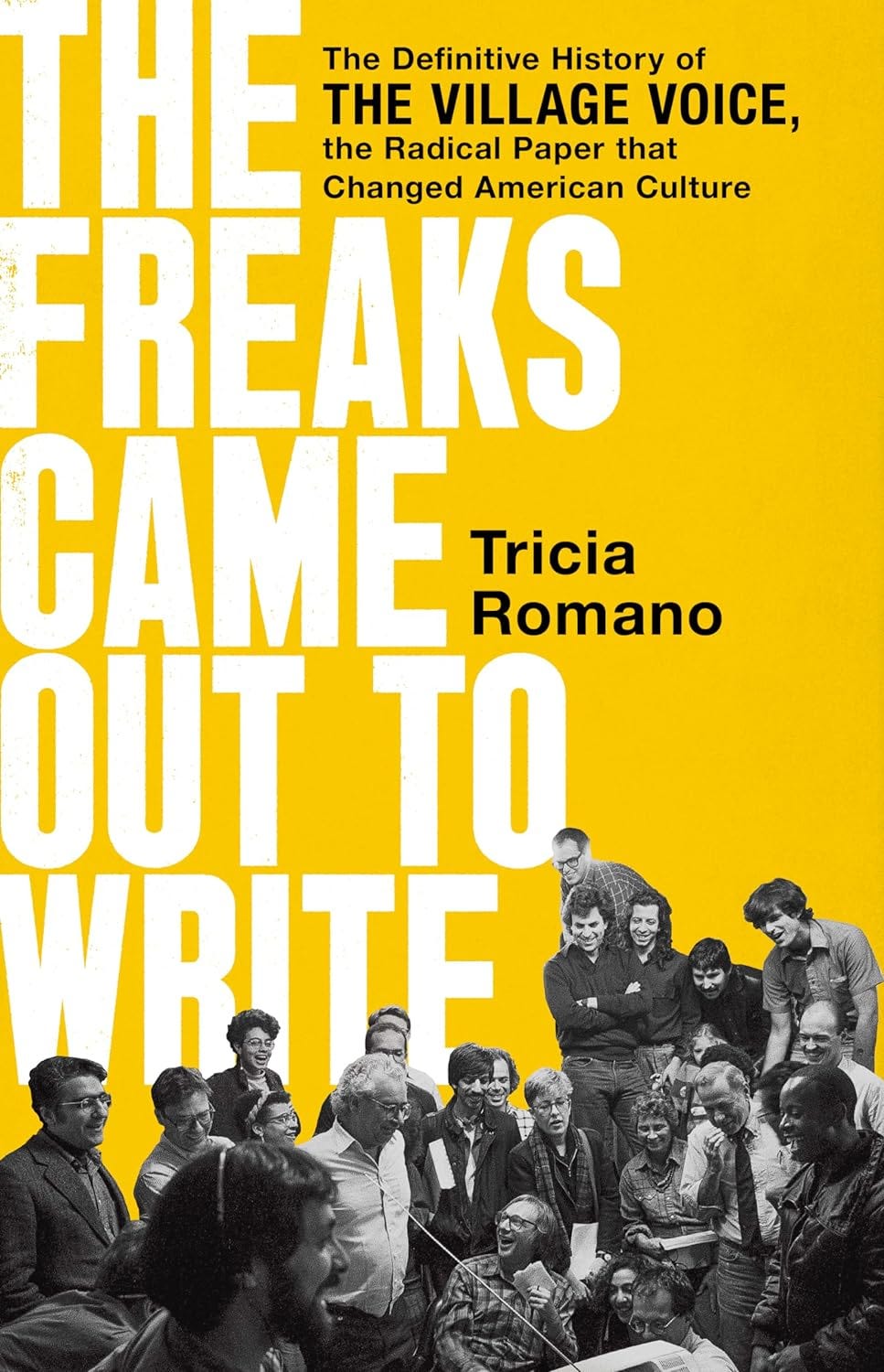

For the past quarter-century, Tricia Romano has been listening to me spout theories and talk nonsense, and I, in turn, have gotten to watch her write a book that will outlast us all. I encouraged her to do it, and helped edit the result. The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of the Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture, out in February, is a major achievement—hugely entertaining, deeply informative, full of amazing pull quotes, not all of them rancorous, either: “The motherfucker was a dream of a writer,” Robert Christgau exults about James Wolcott, the latter of whom delivered the first early report of the CBGB’s scene for the paper in 1975.

Long before the world knew Tricia as an instant-pantheon oral historian (her only one, she swears), I knew her as one of the best writers on dance music around. In 2004, when I was editing the music section of Seattle Weekly, a place where she’d first trained me in five years earlier—see our first exchange below—I commissioned her to write about John Digweed’s Fabric 20, and she turned in 750 words that nailed the entire project to the wall. Her piece was so acute that Digweed emailed her his thanks for getting it right.

Long before that, though Tricia had been a teenage raver in Las Vegas. Here’s that portion of our recent talk. The rest of it—the bulk of it—will appear in a forthcoming issue of Love Injection.

BC: You and I first met 25 years ago this September. I will never forget our first argument, of many. I told you I loved Fatboy Slim as a DJ—this is 1999, when that is a tenable position—and you scoffed and refused to take me seriously until I told you that I equally loved Jeff Mills. A couple years later, you told me, quite begrudgingly, that you had actually finally heard Norman Cook DJ and had to admit he was pretty good.

TR: [laughs] He’s a fun DJ.

You’d been listening to DJs play dance music for a decade by that point; you started raving in Vegas as a teenager. Tell me about that.

I graduated in ‘91, so probably the first years I went to a rave was end of ‘90, early ‘91. It was all the early Vegas raves which were put on by a friend of mine in my high school friend John Tobin. Some of them were warehouse parties, and some were out in the desert. Some of them were in, basically, bars—just a bar that was letting in kids. At that time, we weren’t dressing [in the] raver uniform that you see, like the candy-raver thing, so I don’t think they were like, “Oh, there’s a bunch of ravers in here.” But they definitely advertised with flyers: “X”s, acid-looking symbolism, Smiley faces, all that stuff. That was the beginning. I just loved it. I remember hearing Future Sound of London, “Papua New Guinea,” in ‘91, and being like, “Holy shit. That’s what I really like.”

Did you start getting mixtapes right away?

No, not at all. I didn’t actually buy mixtapes. I was only ever seeing them [DJ] in person. There wasn’t anybody of real note in Las Vegas. Every now and then, they would try and bring somebody to Las Vegas that was from L.A., like Doc Martin. Really, all the big DJs from L.A., they would try and get, but it was mostly just locals. I was in Vegas, doing that for a little while—I was at UNLV for two years—before I left for Seattle.

You were a semi-active DJ when we met. When did that begin for you? How, where, with what records? Who taught you to mix? And was it before you moved to Seattle for college?

I started doing it in Seattle, in my apartment on Capitol Hill—the El Capitan, a very famous apartment complex with, apparently, the most soundproof walls and floors, because I would have parties until four in the morning, pretty much, and I never had anyone playing or knocking on my door that I know. I learned how to play there. When I began, I was playing tech house, deep house, and drum & bass. That was, I think, unusual for that time; a lot of people only picked one or the other one genre and stayed there. And I liked both.

When did you move to Seattle, and had you already visited the city beforehand—and if so, was it to go to parties or clubs?

I moved there in ‘93. I visited in December of ‘92, because I was looking for a place to go to college that was not UNLV; I wanted to transfer. Initially, I wanted to go to New York, obviously, but it was so expensive and too intimidating. That was also the height of grunge in Seattle. Everybody was talking about it, and I thought, “Maybe I might like that.”

I visited Boulder, Colorado; Reno, Nevada; San Diego, which I also really wanted to go. And then I visited Seattle with my friend, DJ Shoe from Las Vegas, and we ended up meeting people right away. This guy that we met, Mike Smith—we’d heard there was a secret show outside the Crocodile [Café] the night before Christmas, and it was breathing. We thought it was going to be a Pearl Jam show or something. It was some weird rumor that we had somehow caught wind up, and we ran into this guy. He was like, “Are you here for the secret show? I don’t think it’s happening.” We smoked a bowl, and then he just basically took us in and showed us the raves.

We went to a NAF rave; we went to another party. Over the week, we went to a bunch of places. Mike Smith introduced me to Brian Felino, who was my freshman roommate when I moved to Seattle. We were just all immediately plugged into everything. Also, the first week I lived here, I met Mario Diaz, who was a promoter in town, but then he moved to New York and later L.A. He was also very big conduit.

I couldn’t afford the state tuition anywhere. So I had to move somewhere, live there for a year before I could apply and get in-state tuition. I knew I would get in because I had high [grades]; it’s easier to transfer after two years. So that’s what I did, and I got into it. That’s why I moved to Seattle, because I figured I could do something for a year to keep myself occupied before going into college.

Your Voice internship happens how long after you moved to Seattle?

Four years.

What was clubbing in New York like versus everywhere else you’d been?

Seattle’s club scene was very small, but more cross . . . what’s the word—mixed, because it wasn’t so big . . .

A mixture of scenes?

Yeah, like goths and hip-hop and skaters and gay and ravers—you would see that more kind of commingling.

The same people at every show?

Yeah, kind of—you didn’t have to be all goth to go to the goth night or the S&M night. You could just go to all of the scenes, so it was a little more exciting. I loved Michael Manahan as a DJ out here more than any of the DJs I saw in New York that were local to New York. I saw a lot of the local DJs like DB and Dara, Soul Slinger—that whole Liquid Sky crew, the NASA people. Later I saw Frankie Bones and Heather Heart. The New York flavor of DJing, the style that came out, it wasn’t my thing. I loved “Papua New Guinea,” I loved Hardkiss, and all that other stuff.

You have very West Coast tastes.

Right, and so deep. And then, the London stuff, the drum & bass, I liked the really hard-edged stuff.

Techstep.

Yeah.

Did you ever feel competitive as a DJ the way you did as a journalist?

No, because I was barely professionally DJing. I was excited to just be able to do it.

When I first got to know you in New York, you were playing at the Tribeca Grand. How did you end up doing that?

Tommy Saleh was one of the people that ran the club program. He needed somebody to DJ. He asked me; I don’t know how that came about. But I needed the money. It was a pretty easy gig—you just had to play chill stuff. I didn’t even necessarily beat match, I don’t think. it was just more like lounge music. It was that thing where every hotel had a DJ.

Well, that starts in Seattle, doesn’t it?

Kind of: Alex Calderwood and the Ace Hotel—they were already way into DJ culture. But yeah, that was the whole thing. They were connected with Wallpaper magazine. It was just an era—the cool thing. I mean, restaurants: I remember there was a restaurant in Williamsburg called Planet Thailand, and there was a DJ! There was a DJ in this fucking Thai restaurant.

Which is a weird place to have a DJ.

Yes! That little trend funded some people’s lives. [laughs]