BC084 - Five Mixes: John Darnielle (June 2024)

The Mountain Goats leader discusses formative clubs and his Mixcloud habit: "It takes me to places that I won’t be going by myself"

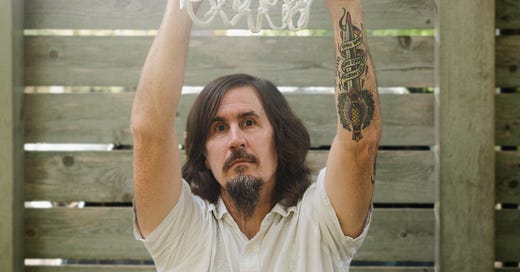

Photo by Lalitree Darnielle

What’s this guy doing here? you may wonder. Songwriter, bandleader, novelist, actor—has John Darnielle become a DJ now, too? Not quite. This interview came about simply because over the past couple of years, Darnielle’s social media feeds blossomed with shows and sets from Mixcloud. And these shows and sets were gloriously far-flung, reflecting his mighty listening habits. There are few music lovers as purely catholic as Darnielle, and it seemed like it would be fun to talk about. The brand-new reissue of The Mountain Goats’ 2000 album The Coroner’s Gambit on Merge gave us the opportunity. (Huge thanks to Colette Arrand for her diligence.) As you’ll see, these particular Five Mixes were chosen basically on the fly, uniquely in the series thus far. We spoke two Thursday mornings ago.

BC: I should start with this: You have a Minneapolis rave doppelgänger. He’s a younger guy, and he is the spitting image of you. I do a double take every time I see him. I think you would be proud. He dances his ass off. That guy works it.

JD: That’s so awesome, man. He’s making good use of his life. I didn’t spend enough time on the floor back when.

I am mainly interested in talking about what I will jocularly refer to as your Mixcloud habit. But I want to ask a little first about your history with DJ culture, per se. Do you remember the first dance club you ever went to?

Oh, absolutely . . . I can see it in my head, but I don’t know what it was called. I don’t really remember why we were there. I was in high school, when that stuff was kind of on the rise. There’s a couple that are doom memories. But there was one time we went into L.A., I forget why, and it would have been in peak new wave time, ’84 or so—not, like, guitar new wave.

Synth new wave?

Do you remember what MV3 was? Nobody knows MV3. This is a long spiel, but you may not know this—most people don’t.

So, because the television stations were so powerful in Southern California, we didn’t get MTV at the same time as everybody else did. The whole nation had MTV, and we didn’t. So, in SoCal, radio stayed much stronger for another year while negotiations took place. But the way that the local TV stations took advantage of this was, they would put on shows, like an hour-long show or half an hour, five days a week, of people showing videos, and there was a show called MV3. It hosted by Richard Blade. It was five days a week at, like, 3:30—so as soon as you got out of high school, you go home, and turn on the TV. It was in some club in Orange County, I think, and they would just show videos and—this show was like American Bandstand—they’d show the people dancing. And of course, we would Beavis and Butt-head it all day. You’d see two or three videos in the course of this. They show the “Stand and Deliver” video by Adam and the Ants; we were excited about that. And they were also pushing local bands like Felony, who did a song called “The Fanatic” that was big on SoCal radio. That was the club environment—people who were early-video-exposed and people with big new wave hair.

So, I went to one of those at some point in, I think, ’84. I remember they were still playing “The Safety Dance,” so it might have been ’83. Men without Hats—or, as we liked to call them, Men without Hope. [laughs] New York would often get stuff first, but it would blow up bigger on our end, because everybody was buying import 12-inches.

The power of KROQ.

Yeah, KROQ was so huge, but also the stores, like Zeds and Bleecker Bob’s that we had there; Middle Earth near Norwalk.

So it was that club, but my main relation to club culture is ’85-’86. In Portland, I looked like a certain sort of person, and people would approach me, and somebody approached me to sell me weed, and said, “Hey, do you go to The City?” This is a meaningless question: I think I’m in the city. “No, the City is a nightclub. You should go.”

So, I did. They told me where it was. From the perspective of an adult life that seems so strange that it even happened, that some stranger approached me and told me about a nightclub. I had nothing else going on, so I [went].

This is an all-ages, mainly gay—it was gay-focused; anybody was welcome, but it was a queer nightclub in Portland, run by a guy named Lanny Swerdlow, who is still out there changing lives. He’s become a registered nurse and does medical marijuana education—he’s a prince of a human being. But he was running this club for all-ages queer youth.

I didn’t even realize at the time—you take it for granted when you’re a kid, right?—but it had an astonishing sound system. All I knew was that it sounded bitchin’, but I know now, with perspective—oh no, they put good money into the system. It was four nights a week, Thursday through Sunday, 10 to 3 on Thursday and Sunday, and 10 to 4 on Friday and Saturday. And I would show up pretty close to doors and stay till close. I was a wreck. And for me, the time on the floor was freedom. I could get out of myself.

It was a time when the City existed in a sort of tension with a club called Skootchie’s that was a normal-people’s club, that had a sign on the wall that said, “No overtly homosexual behavior on the dance floor.” The City responded to this with a sign that said, “No overt heterosexual behavior on the dance floor,” which is amazing.

People have been trying to make a documentary about the City for a long time. Like most good clubs, it’s almost impossible to understand if you weren’t there. But a dance floor—there’s so many narrative arcs and friendships are formed and lives are changed.

I remember there was a queer youth meeting—you could get a dollar off admission to the club if you came to the meeting. So, I’d be at the meeting, and then the meeting would let out, and you’d hang out for an hour until the club was actually open, and the DJ would be warming up. I would just go out on the floor and dance by myself. This is the first time I ever heard “Let the Music Play” by Shannon. You ever heard that on an amazing system? Make it a life goal. I remember this happened—fall 1985. I remember it with clarity, because when the Linn[drum] comes in—it just freaked me out. It was so good.

The City changed and saved my life. I’m always saying, without the city—I would have found other things to do with my time, and they would have been very destructive. I had the experience of being messed up and not terribly friendly, but welcomed in a dance club. That’s my relation to club culture.

Was the City the first place you heard beat-matched DJing?

I think so, actually, because the other one that I’m talking about, where they played “The Safety Dance,” I feel like that was still when the song would end and people would clap, American Bandstand-style. I don’t remember the songs flowing the way they would do at the City. It was for sure the first place I heard the exclusive DJ 12-inches that that you couldn’t buy or hear elsewhere. One big record at the time was ABC’s How to Be a Zillionaire, and there were 12-inch versions of “Be Near Me” that you didn’t hear on the radio or anything, that went on forever. Oh: “Erotic City,” Jesus fucking Christ. Hearing that thing on a good system, you can imagine, right?

Yes, absolutely. Now, everybody knows you’re a musician. But you’re also one of the most ardent listeners I know. When did DJ sets come into play for you as a listener?

Like, in my daily life now? It’s funny, because I come from a pretty rockist point of origin—very into the album and stuff. And then learning to unlearn that way of thinking, or to broaden my perspective, it becomes a lifelong errand, because of the twelve-year-old I once was. My twelve-year-old self was obviously waiting for the album, and resisted when 12-inches became a thing: “Wait—it costs too much money.” Yeah, but it’s its own thing.

Now, when I’ll be looking for something to listen to, it’s like, “Go look at your Mixcloud.” The thing about Mixcloud—SoundCloud’s great, too. There are Mixcloud people, I’m sure, who like say that the glory days are past, it isn’t as good as it used to be. I don’t know that that’s true, really. They could be right. I don’t know. [laughs] But now, the wealth of musical experience you can have when you go to Mixcloud and stay there for a couple hours—it’s shocking. It takes me to places that I won’t be going by myself. I have to keep a good, broad diet because right now I’m subscribed to too many trance DJs and they upload, like, nine things a day. You can wind up in a big long Eurotrance thing.

But I found some doom guys—there’s some very good metal DJs there. And there’s a lot of different kinds of house. Also, if you go to look for Croatian-Serbian DJs, there are people really mixing it up, who will do a mix of minimal house followed by a mix of Kris Kristofferson-style country. In Europe, the sort of genre partisanship, that was a thing that Americans have always practiced: “I listen to rock,” or “I listen to rap”: When I went to Germany in ’95, I was noticing that the indie kids were also listening to dance music, and over here, the indie kids took a long time to really go, “Oh, there are other kinds of music.” A lot of the European Mixcloud people, I think, are sort of like that, and say, “Well, now I’m doing I’m doing a country thing today.”

Do you recall if there was a particular show or set that you got you going on Mixcloud? Were you there for one thing and thought, “I’m gonna see what else is on here”? Or did the algorithm take you away?

I think I was curious about it because I had seen somebody share a number of mixes at some point, probably on Twitter. I wonder if my follows show who my first follow was? [John looks at his Mixcloud page.] The first person I followed, it looks like, was a [page] I haven’t seen in a long time called UK Vibe. But Lefto Early Bird had, I think, a Schoolboy Q track that I wanted to hear that was exclusive to them. I still follow them. [browsing follows] Shy C, classy DJ. . . . But I think that was it, actually—that was at the time of the Black Hippy stuff being kind of big. There were a couple of DJs who were getting exclusives, and I was wanting to hear that.

I also was listening to Terre Thaemlitz—I was getting into their stuff. They have a lot of essays about what house music is, the deeper meaning culturally, socially of house music, and I started to think, “Let’s dig deeper and see what’s going on.” Before that, I used to buy stray house stuff on Forced Exposure, just at random, and really enjoy the positive, like Kaito, the really sort of uplifting stuff. That constitutes a lot of the Mixcloud stuff now.

Are there particular accounts you pay close attention to there?

Takanome is a really great account that does mainly house. But really, for me house is a genre for music obsessives, because you can say, “Oh, well, this is really kind of tech house. But it’s also a little progressive.” You can draw these very fine distinctions that I really don’t think I have the skill to actually draw, like the chops. But I love that you can hear it, if you have a DJ who’s very proficient, who can say, “Here, I’ve got a mix that does this. And here’s this other one—it’s the same style of music, but it’s in this other little zone. Takanome is really good with that.

I follow Scottieboyuk; I think he may have stopped posting, but he’s great. [continues browsing] Let’s see here—oh, low light mixes. Those are incredible. It’s ambient. And this Croatian fellow, zvonimirmarković, that I was talking about, is very eclectic, all over the place stuff.

There’s also a lot of disco. I don’t have the standing really to say that disco’s having a moment, but it really does feel like a lot more disco crosses my desk—the Fun Monster Orchestra, I think they’re called—that kind of stuff. I heard that song first on a mix, and then I heard it at a casino in Vegas, like six months ago, which was wild, to have my Mixcloud stuff out [in public].

Mixcloud feels kind of private to me, in a way. It’s like, most of the stuff I hear there, I don’t hear people talking about otherwise—although also, I’m a senior citizen. [laughs] I don’t hear people talking, period.

Oh—Rabid Acid Badger. Do you follow that guy?

I don’t. I’m mostly on SoundCloud. It ends up being the snake eating its own tail, in a sense, because it’s very easy to just stay in one place. I can make playlists pretty easily that way. Also, there’s also the fact that on Substack, you cannot embed anything other than a SoundCloud link or a YouTube link. But Mixcloud is just as much a place for radio stations, or the like, to put their archives. So, when you’re touring, do you play sets for yourself or do the others on the bus hear them as well?

Not in the age of the earbuds. That was so much a thing in early touring—you’d spend the week before tour making a mixtape or two, when you had your turn to throw it into the car stereo. Now, there’s not a lot of listening to music together like there used to be. In the front lounge, people watch more TV.

I wake up early, and I make mixes for myself in the front lounge, and I share them with our driver, who’s a guy named DJ Smooth who actually is from Queens and literally was there at the birth of hip-hop. He got out his turntables for a show of ours in Lawrence and just DJ’ed for us during the time between load-in and set. This is my dude; Steve is his name. But yeah, I play for him. Mainly, I make jazz fusion mixes a lot. A lot of jazz stuff is what I’ll be listening to—it’s morning listening, right? But I’ll get up, I’ll put together a ten-song playlist, and I’ll put it through a little tiny Bluetooth speaker, usually, called a Wonder Boom [laughs] that I carry with me, a $39 thing.

We used to, back on the Kaki King tour, I remember being in the back lounge doing a DJ thing. When we do that, it’s usually a sort of a pass-the-phone-around thing, or somebody keeps it for three tracks or so. That’s actually how I first heard—I wasn’t paying any attention when Daft Punk was having a big moment at all. And Jon [Wurster, the Mountain Goats’ drummer] got the phone at some point where we listened to music at 2 in the morning or something and played “Get Lucky.” That’s pretty good.

That’s awesome. I want to ask about specific favorites shows or sets.

I have to look at my Faves to remember this . . . Let’s see here . . . Afrobeat . . . Arimak . . . This is what’s great about Mixcloud. One of my favorites: Radio 3 In Concert, Beethoven: Missa Solemnis, Sir John Eliot Gardiner, 14 March, 2022. Incredible.

Soul Roots [Radio]—you ever listen to Soul Roots?

No.

Oh, man, it’s reggae out of England. One thing is—and this is so bad about internet DJing—that there’ll be the thing where it’s either voice or music, so the voice comes in, and the music just goes away completely, instead of talking over it like a DJ. And sonically, I find this incredibly distracting.

Five of John Darnielle’s favorite Mixcloud sets

[uncredited DJ], Hot Night, December 1979 (The Pine Walk Collection; uploaded 2022)

They’re doing the Pine Walk Collection up there, right? I wept like a child with that stuff. [laughs] That’s a service to history. But the thing is, I think a lot of Mixcloud is kind of a service to history in that way—it’s focused on the mix, so as long as that stuff stays up, it is a testimony to something that . . . Back in the clubs, when you would have a good night out in the eighties, you would philosophize and go, “There’s no record of this, except in our hearts, and no one who wasn’t there can understand. It’s ephemeral.” And that is true, and it’s still true. It’s always going to be true: communally experienced music can’t really be reproduced or expressed. But there’s something like that, that can take place, if there is an archive of mixes made that people listen to. Even if they’re not listening together—the togetherness is the important part of the club, right? That we’re on our own. We’re both experiencing existential things that that can’t be shared, but also communally having all that happen at once. This stuff is so important. . . . Yeah: Hot Night, December 1979 is a very good time.

There’s so many in that collection it’s almost an unfair question to ask for a favorite.

Giancarlo, Breakfast Music, March 1980, is really great. That was really fun. But all of those, I like that they have dates next to them. It’s so important and great. You can go look at the charts and see what else was going on. You can look up the news of that month. Yeah, it’s an incredible service to history like that. Those, whoever has them—I don’t know what their status is now, [but] those need to be preserved in a museum.

DJ2tee, Dance Floor Jazz 2 (March 2024)

Man, that is such good stuff. You remember the moment when Soul II Soul was on the charts a lot? Jazz flute being part of the conversation. And there is plenty of flute house. There’s plenty of that kind of stuff. But I don’t find that much in terms of mixes of it, and I remember that one was a mellow and amazing mix. And mellow is kind of a lot of what I seek out for my life these days. Although [laughs], also, the new Ulcerate album [Cutting the Throat of God] is incredible. But yes, for jazz, that thing is extremely good. It’s got Seawind on it, I think that’s how I found it, which is a sort of jazz [group]; Mandrill, and a bunch of older jazz-rock stuff.

I don’t want to romanticize the seventies. But there was enough money kicking around the record business that you could get a contract and tour, playing jazz-rock with a 12 piece act, right? That’s not really even feasible now. There’s only room for one or two—you get the Daktaris or whoever. And it’s great, but it was way more possible for a bunch of people to play sort of, not out music, but stuff that wasn’t actually going to chart, stuff that was more useful for dancing to, or having a good time to. And that music is really [at] this sort of jazz-rock moment where it’s like, they’re jazzers, but they’re also not demanding a lot of attention as soloists. I happen to like the soloists, also, but the jazz-rock moment is pretty cool.

Robbie Leslie, New Year’s Eve 1988 at Probe, Los Angeles (uploaded 2022)

This one seems to tie into what we were discussing earlier a little bit.

Yeah, I think I was trying to find a New Year’s that I actually spent in a club in L.A., and that wasn’t it. But that’s how I wound up there. It was at Probe. I feel like Probe becomes a club I may actually have played as the Mountain Goats. The probe was a short-lived place, I think. I mean, most L.A. clubs were. I was also interested in that one because by ’88, my attention is elsewhere. I’m not listening to dance music. It’s to my lasting shame, right? There’s a lot of interesting stuff going on. But I’m listening mainly to, probably, the Pixies at that point, and the Gun Club and Celtic Frost and KNAC, the [Los Angeles] metal station. It was pretty new wave, still, is the thing I remember.

In the comments on here, Leslie answers somebody by saying that a track is 10 Heaven the calling 1986.

Wild. Yeah, this is the last song [of Leslie’s set]. Released on Airwaves Records, a small indie label out of L.A. If you, as a DJ, get people to actually hear something that languished in the bins forever, and they don’t just hear it, but to have a good time hearing it. That’s the greatest thing. I mean, listen to the top of this mix. [Plays it over the phone: long hard drumroll with bells and a breathy woman’s sigh] It’s just incredible. I thought, “That is an amazing way to begin your mix.” But also, it’s the first song of the night on your New Year’s Eve mix. So not that many people heard that. It’s like, people showed up later, an hour into the mix. It’s like a Grateful Dead show. The meat is halfway through. But I’m really obsessively focused on first tracks and stuff like that, on how things begin. And that opening there—a big eight-bar drum fill and then bells. Fucking spectacular.

Krish Raghav, Play That Afrobeat, Mr. Raaja (uploaded 2023)

Yeah, look at the cover. Look at the skull on the train, and you’ll have your answers to how I wound up at that. But the description is: “One of 12 mixtapes connecting the music of my childhood (Tamil pop) and the music that influenced me (sinophone indie) to the music of my new home, the Netherlands.”

How many connections can you have?

A lot. And the thing is—remember when, if you were curious about global music, either you could make it your mission in life to learn more, or you could hope you got lucky and ran across stuff. It’s so corny to say, but the internet, for all the terrible things about it, the miracle of connection, of being able to access music that you would have . . .

You and I are very similar like this. I have a bottomless curiosity that music. There is no kind of music I don’t want to know about—at least to understand a little something about it. And prior to the internet, you either had to make a study of it or hope you ran across something. And now I can listen to this guy, right? To his 12 mixtapes, and get an actual education. A really enjoyable education. He doesn’t have a lot of followers, it looks like, but yeah.

This tracklist is jaw-dropping. I’m just like, What the hell is this going to sound like? I know a couple of the individual songs, but never in my life would I have expected them to show up in a thing like this. The Stereolab song? I’ve always wanted to hear somebody play it like this.

Well, it also speaks to how . . . I don’t think it’s like it was in the in the rock era. But I do think there’s plenty of people who haven’t pause to think about how DJing is an act of artistic expression, that to curate, to play songs in a sequence, and to choose those songs is to give them context, and to place them in relation to one another. And it’s as creative and act as any other musical act. This guy’s stuff really speaks loudly to that. You get a very personal journey through music; you get to share in somebody else’s extraordinarily personal vision; and also contextualize it in your own listening.

To me, there’s a thing about music: What it does is it puts you in touch with infinity, right? You get to be inside infinity and locate yourself at a point in it—but also be able to see all the other points on the grid. That’s what mixes like this do. They draw your attention to the infinite, to the eternal nature of the art form you’re engaging.

I’ll go actually go you one further on that. For younger people, DJing is what folk music used to be. It’s passing the guitar around.

Yeah, totally. No, that’s right. That’s exactly right. Because it used to be if somebody came to town with a guitar, maybe he knows some songs we haven’t heard. And that’s a big old deal in the in the in the pre-[smart]phone age. Sheet music would go around—the sales of sheet music, it’s hard for people to contemplate. If something was printed, that meant you had something new that people in New York were playing. They could really be connected by that, in that way.

The sheet-music era’s fascinating in terms of its sales, because there were blockbusters then. There were 3-million sellers, 10-million sellers.

When people go into music stores—like, if you ever watched Pennies from Heaven, that’s what the main guy is doing. His job is trying to sell sheet music to stores.

Radio 3 In Concert, Beethoven: Missa Solemnis, Sir John Eliot Gardiner, BBC Radio, March 2022

I found this on a day when I was thinking about Missa Solemnis. Because Missa Solemnis is a piece that is the subject of a lot of hyperbolic discussion. I think Adorno is the one . . . I think it was his favorite Beethoven piece. He may have said like, It was the the end of music or maybe he hated it. He wrote an essay on it. There’s some major pull-quote about it. [looks it up] “The Missa was entirely different puzzling to Adorno, who agonized over two questions. One is, the paradox of Beethoven composing the mass at all. This really is a paradox. He’s a classical composer. The very existence of the work is a scandal and Adorno would like to understand fully why he did it. The other question is how he did it. That was a unifying dynamic poll, that was an exploded form.”

The Missa doesn’t have doesn’t have a single recurring theme, or a cluster of them. At that point, in classical music, you’ll hear a [hums main riff of Beethoven’s Fifth], and that will be called back to in the last movement, right? The same as in a pop song, when there’s a little [hums] “Da-da-da-da!” Nile Rodgers is great with this [kind of] guitar figure. It goes through the song, but it hits a key point, it calls you back, it gives a unity to the piece. And the Missa doesn’t have that, which is quite incredible for high period classical music. It’s kind of shocking.

But also, I’m a lay listener. This is not something I’m going to notice if you don’t point it out to me. I’ll be listening to it: “This is pretty wild.” But I won’t have the language to describe it until I engage other people talking about it. So, I have to listen to things three times, where I think a more connected classical listener [wouldn’t] really need to do that.

So, I was obsessing about the myths and I listened to a bunch of different versions on that day. And it turned out that that feed has all kinds of great stuff, just tons of, and I was finding programs about classical music that are good. You know, we all have a good local classical station, probably. But also, you know it’s live and you can listen, you can tune in and find stuff. But something like this enables you to check it out from the library at will and revisit it until you get it right, which with a piece like the Missa, you absolutely have to go back to it a couple times, and read and do stuff, which for me is a pleasure. I think for some people, there’s a passive element to music, which is fine, too. But for me, I take a lot of pleasure in trying to figure out stuff. We’re trying to understand what other people are talking about musically.