BC102 - Television and Tom Verlaine, mixed by Ty Burr: Marquee Moons 1974-2019 (YouTube, November 22)

Starkly lit black-and-white can be every bit as hallucinatory as projected color oil blobs

Ty Burr is a film critic by trade who worked for a long time at the Boston Globe and now writes for The Washington Post. In 2012, Burr authored a very smart book titled Gods Like Us: On Movie Stardom and Modern Fame. I bought it at St. Mark’s Books after pulling it off the shelf and giving it a flip-through. I typically expect the worst from those kinds of summation titles; they often deliver a bill of goods, or worse, soundbites. Burr doesn’t—he has ideas and research galore, and his writing is both enjoyable and not facile—a rare thing, especially a decade-plus later, when the latter is in overwhelming supply. I sprinted through that book; I should find it again. I bet I’d get even more from it.

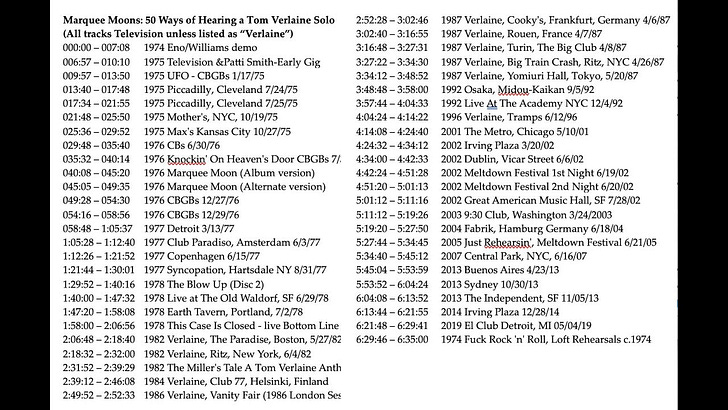

Burr is also responsible for compiling this monster: “45 years of ‘Marquee Moon’ Tom Verlaine guitar solos edited into one 6 1/2-hour supercut,” Burr wrote on the YouTube page. “Because the world needs it.” Or, as my man Nate Patrin put it, “It’s the most amazing idea I’ve heard since Hit ‘Em.” (Hit ‘Em is a subgenre literally dreamt up by Drew Daniel of Matmos and The Soft Pink Truth—a compilation just came out; its notes tell the story.)

One obvious comparison is to Grayfolded, John Oswald’s epic mixdown of dozens of versions of the Grateful Dead’s “Dark Star,” where he doubled-tripled-quadrupled voices and eras on top of each other—young and old Jerrys harmonizing on the opening line, air-melting guitar-solo bits played back-to-back-to-back—for two hours and change. But what Burr does is more akin to another, similar project: Dark Star 1972, made by somebody also calling themselves that, which strings what its maker dubs “the jam sections” from thirty versions of the song performed that year, one after the other, to delirious effect.

This compendium of “Marquee Moons” achieves, and archives, something equally dizzying. Starkly lit black-and-white can be every bit as hallucinatory as projected color oil blobs—cf. Hundreds of Beavers, one of my favorite films of the year. And hear this monster out—it’s not a stunt, but an argument. Good criticism comes in many forms. This is a prime example.

The argument is basic—Verlaine was a master improviser, and here are fifty variations on a theme that prove it. (I’m sure somebody has done this for Sonny Rollins solos or something, right? Hope so.) And while there may have been nights that Verlaine sleepwalked through the “Marquee Moon” solo, and that would be his right—I’m sure Burr went through more than fifty shows to make this thing. (He has to have, right?) But the tinkering, stretching out, wrestling, stoking, and burning through the solo gathered here is often breathtaking.

I almost wrote “torturing, caressing” in there—a line directly taken from a Nels Cline quote from Franz Nicolay’s amazing Band People: Life and Work in Popular Music: “[P]laying certain kinds of Wilco songs, in my mind I’m going to a classicist kind of approach . . . and Jeff [Tweedy] will say something like, ‘Please don’t be so reverent, ’cause I want you to go against the grain on this.’ That will be hard for me, ’cause I feel like then what I’m doing is putting my own so-called stamp on it before I’ve even really learned the song inside out. I don’t want to start destroying the song before I’ve caressed the song.” An understandable dilemma. I hope I’m not being facile by suggesting that, over and over, that’s what Verlaine does here—caresses and tortures the solo, both at once.

Is it wrong of me to be mildly surprised that Verlaine took the solo a lot further out, on average, at his solo-billed shows rather than he did early on with Television, much of whose pathbreaking rep is predicated on how far out he would take songs like “Marquee Moon”? I shouldn’t be—improvisers do lots of things lots of ways, and Verlaine seems to have been allergic to repetition that didn’t crest in some way. And being the undisputed leader—even after having been the undisputed leader, only without his name on the front—would seem to offer certain advantages as well. Sometimes Verlaine plays it pensive and eerie, but more often he’s dressed for battle.

Yet, without looking, I could absolutely tell when it was Television again (4:14:08)—Billy Ficca’s drums on the breakdown are unmistakable; no one else plays it exactly that way. I noticed it during what I’ve always privately dubbed the waterfall sequence, the cascade of single notes that follows the hard 1-2-3! 1-2-3! section—a part that occurs rigorously, played without much variation, a pole that centers the music. It also acts as a signpost for the mix—a point of reference, a rugged peak that subsides into jagged soapsuds. From a whisper to a scream to a whisper again, as reliable and purpose-built and serially climactic as a good techno set. One niggle—the versions’ visible tags frequently do not match the playtimes written on the screen. [EDIT: Burr is rectifying this.] Otherwise: wow.