BC131 - Five Mixes: Peter Shapiro, R.I.P.

Looking back at pivotal music writer through the DJ sets he championed

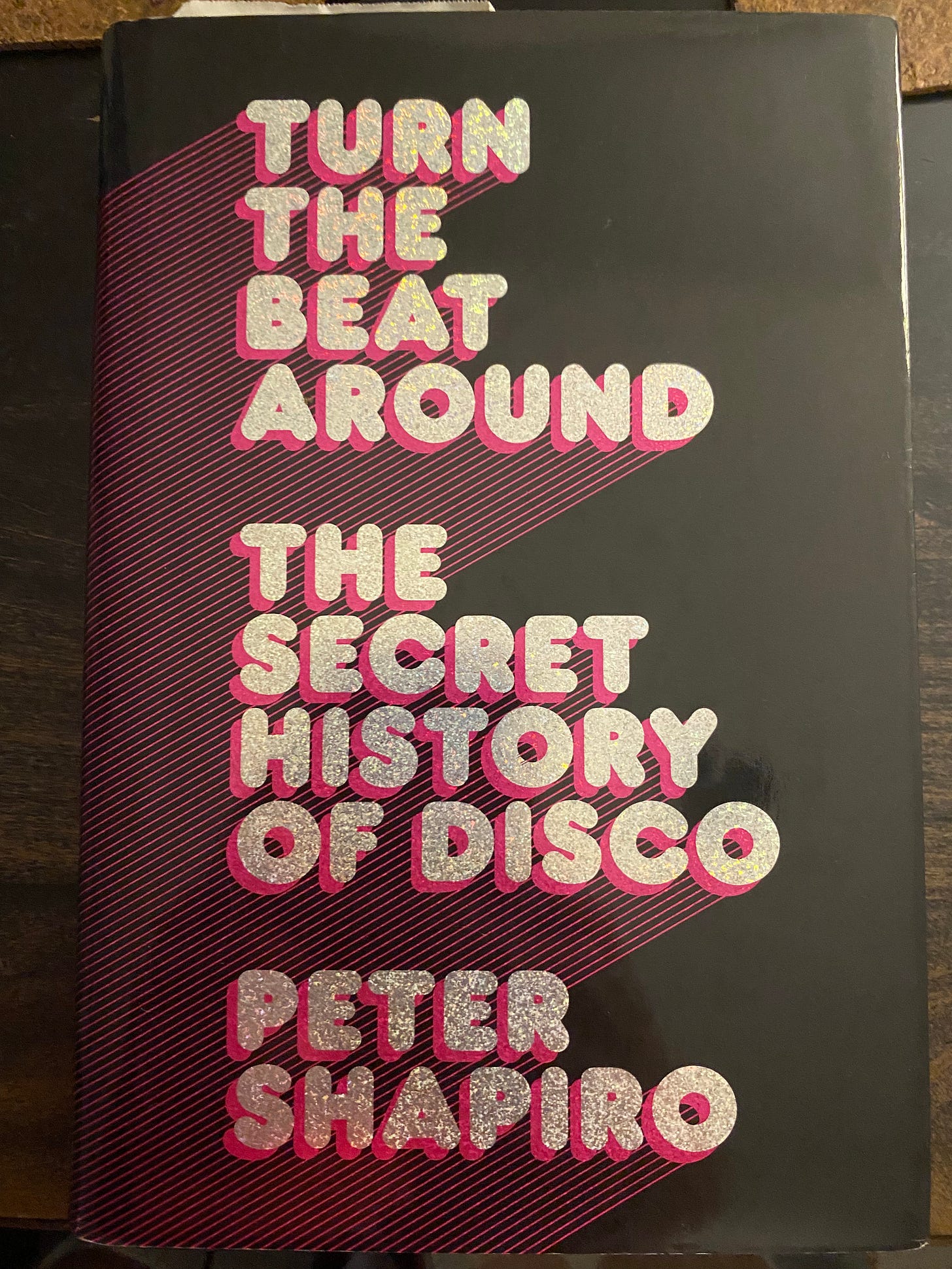

I remember when Peter Shapiro told me he was done writing about music and had undergone the process of becoming a corporate lawyer, working at the time (this was the mid 2000s) for General Electric. There was already a panic on about the sustainability of working for the music press, and Shapiro had a family, so the decision was made for him, in a sense. He’d already turned in his book, a grand summation of his life as a listener called Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco, published in 2005, a year after Tim Lawrence’s Love Saves the Day earned accolades as the definitive word on the subject. Those books to me are coequals—as my colleague Alfred Soto put it, they complement each other. Lawrence’s deep dive into the New York seventies unearthed amazing quotidian details (a tour de force three pages on a sound system) that matched or topped the glamorous ones that had been the meat of Anthony Haden-Guest’s The Last Party, his chronicle of New York nightlife centering on Studio 54. He made disco seem both everyday and world-shaking by focusing on neighborhood and musical details. Shapiro’s book goes the other direction; it offers a sweeping, thrilling overview—detailed, offhand, trenchant, loaded with specifics, the writing thrill-a-minute, as usual.

By the time Turn the Beat Around came out, Shapiro was done—in The Wire, his truest home as a writer, he would contribute only fitfully after the mid-2000s. It seemed baffling to me—someone that purely skillful was surely being his truest self while writing overview of James Brown and Fela Kuti, or quizzing musicians on other people’s records for Invisible Jukebox features, from Caetano Veloso to Bill Laswell to a truly amazing round with Lemmy of Motörhead. Shapiro played him ZZ Top’s “Tush,” and gingerly brought up the riff . . . “Oh, I stole it for ‘No Class,’” Lemmy piped up. “Yeah, I stole it blind, but we didn’t go where they went after the riff, so that’s cool, I suppose.”

But being one’s truest self seldom pays the bills. Just ask the burningly intense musicians Shapiro wrote so smartly, so beautifully about, the ones he made amazing jokes about, jokes so good and so obvious in retrospect that you got mad you didn’t think of them first, as when he concluded a Rough Guide to Hip-Hop entry on Puff Daddy by typifying his move to the Hamptons as going to “live by the sea, like his magic dragon namesake.” Shapiro was so loose on the page, yet nothing was haphazard and nothing about it was lazy.

In the mid-2010s, Peter came to my birthday party—a small but potent gathering of writers and friends, and his presence there, among others, felt like a true honor. At one point, I asked about an incident he had written about, where he’d nearly been assaulted until he demonstrated his rap knowledge to some tough kids. When I asked about it, he flinched. I regretted it almost immediately, because what I had read, through Shapiro’s dazzling style, was something very different than he’d experienced. It was clear right away that this had not been a fun experience for him, as it was for me as a reader, but a terrifying one—one I felt foolish for not recognizing earlier, because I knew that kind of situation myself, of being an outsider not only in terms of taste or composition, but as the subject of acute and present anger. Lucky for me, he shook this off quickly, and the evening kept moving. But I never forgot that moment.

I have written about Shapiro’s impact on my listening before in this space, when I covered Daniele Baldeli (cf. BC068)—specifically, another late Wire piece about cosmic disco, from The Wire 318 (August 2010)—so I’m skipping it in this round-up. With the exception of the first item, these are credited the way Shapiro did in the three Wire Primers in which he included them. They’re hardly the only DJ sets he wrote positively about, and they won’t be the only ones I look back upon here, either—stay tuned.

You can hear all five sets below at this YouTube playlist.

Afrika Bambaataa & Jazzy Jay, “Death Mix Pt. 1 & 2” (Winley 12-inch, 1983)

(I know, he’s persona non grata. But there’s no denying the history with this one.) The first and last items on this list came to me via the same source: Shapiro’s “The Primer: Turntablism,” from The Wire 179 (January 1999). They’re also the two items here I’ve lived with longest—since 1999, when he wrote them up and I ran out to acquire them. The first items in that piece are “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel” and this one. “If you were in New York in 1981 you couldn't escape ‘ Wheels of Steel’ even if you wanted to,” Shapiro wrote. But the record he pairs it with was:

Even more underground, in terms of its provenance and the number of people who actually heard it was . . . a bootleg of Afrika Bambaataa and Jazzy Jay playing a party at the James Monroe High School in the Bronx. Possibly taped sometime in the late seventies (there is no offical recording date), “Death Mix” was first released in 1983, two years after 'Wheels of Steel' . . . If it lacks the sense of danger and possibility in Flash's high-wire act, it sounds even more raw and, in its way, just as immediate. It has diabolical fidelity--the cuts and scratches sound terrible--but that only adds to the feeling that “Death Mix” is hip-hop's equivalent of cave painting. In fact it sounds primordial, and since you can't hear the crowd, there's an eerie, palpable sense of ghostly absence in the record. Since “Death Mix” is more concerned with keeping the beat going, obliterating the kind of montage cuts and bold scratch-strokes employed by Flash, it is the only sonic evidence we have of the kind of sets that Kool Herc might have played in the mid-seventies.

At this point, enough vintage hip-hop mixtapes have appeared online that this reads somewhat overblown. But whatever: “ghostly absence” is precisely right—spookily so, aptly enough. And the cuts and scratches’ off-ness, audio-wise, is a good deal of why it resonated. According to Jazzy Jay—interviewed in 2002 for the British hip-hop zine Big Daddy no. 11—both he and Bambaataa are cutting the records on “Death Mix.” “From the sounds of it, then, he was rocking the bits from ‘It’s Great to Be Here’ and you were rocking the ‘Strategy,’” the interviewer posits. “Right. Yeah, that was a good day,” Jay replies. “His style was more mixing records back and forth and I was a lot of cutting-up and quick-mixing and all of that.”

Latin Rascals, Pacos Supermix with the Latin Rascals (Happy Bday to Julinho Mazzei--The Kid from Brazil) on 92 WKTU FM NY NY USA (December 9, 1984)

Latin Rascals, 98.7 Kiss-FM Mastermix (1985)

My collection of The Wire has a lot of gaps and is far from complete—I wound up getting rid of 1996 to 2001 issues for space after moving to New York from Seattle, and I also rid myself of the subsequent issues up to 2009, when I left Seattle for New York again. And my shelves show more gaps beyond that, after about 2021. Therefore, I had entirely missed Shapiro’s final Wire contribution, in issue 425 (July 2019), “The Primer: Latin Freestyle.” It’s walloping as ever. Two squibs from the intro:

Essentially an untrained singer singing an actual song over an electro beat, freestyle can be seen as the Thermidorian Reaction to this shock of the new: a reassertion of the age-old virtues of teen pop (melody, verse-chorus-verse, puppy love) to temper the revolution.

and

Freestyle was the first postwar dance genre with vocals that didn’t originate in the black church.

The Latin Rascals, the duo of Albert Carbrera and Tony Moran, were New York radio regulars whose sets became as beloved among tape traders as the more straight-up hip-hop shows of the time (cf. BC014). In the same issue of Big Daddy—number 11—quoted above is a lengthy interview with Cabrera. “I got inspired by Shep Pettibone,” he explains. “He was on Kiss, a New York radio station.”

I just liked the idea of using records differently. So right there I got to turntables, you know, extra cassette decks, and I started to get into mixing up records. But not from one record to another—I liked adding on extra stuff that was pretty technical, doing stuff that was impossible to do live and creating mastermixes. That's how I got started. Then I was sellin' tapes, doin' parties here and there. Then I visited a record store to play these tapes, and this guy Carlos DeJesus heard one of the mixes and asked if I would wanna hear it on the radio. And that's how it started.

He began doing edits using the pause button, unaware until he went into a studio with Pettibone that you could do it with razor and tape: “I thought the tape’d be damaged if you touched it,” he Cabrera told Big Daddy. He and Tony Moran began making 25-minute sets for the Paco show, “as many as [they] could,” since they aired daily: “Because ours were very technical, it took a long time.”

You can hear what he means on both of these. The December ’84 set is riddled with sharp double-time edits and cunning layering—a sped-up and re-layered “Dominatrix Sleeps Tonight” into “Knee Deep,” for example—while with the longer ’85 mix, Shapiro calls “the passage at around 38 to 51 minutes, beginning with ‘Crash Goes Love,’ is about the most exciting thirteen minutes of radio you are ever likely to hear.” He’s not wrong; he also cunningly neglects to mention precisely which Arthur Baker production with Latin Rascals cuts forms much of that section’s spine, as will I—I’m, cough, out of time.

Röbi, Roli, and Claudio Pavan, Speed Air Play Ultra Noise Christmas 1986 (Special cassette; aired on Radio Lora, Zürich, December 25, 1986)

I was all too ready not to have this embedded here. It took me a couple of days to locate not only a link to the show, but evidence that, by the title above, it existed online anywhere else than in Shapiro’s “The Primer: US Hardcore,” from The Wire 349 (March 2013), another of his rare late pieces. I kept at it because I knew I had seen/heard it before—and also, I had mp3s of the tape from years back that I was willing to share privately with anyone who DM’ed. Happily, I don’t have to. Though the proviso is that the YouTube above removes four of the songs for copyright reasons—gee, that’s too bad, it leaves us with only, oh gosh, eighty-nine others.

Speed Air Play was an hour-long biweekly hardcore radio show that aired biweekly on Radio Lora (MHz: 104.5) in Zürich, Switzerland hosted by a trio of lifers, per Brob Tilt’s Tapes: “‘Röbi’ Robert Zollinger (Timbuktu Nachrichten/ Der Sensenmann fanzines), ‘Roli’ Roland Brümmer (Skatecore fanzine) and Claudio Pavan,” who were “straight-edge and incredibly enthusiastic about HardCore as a lifestyle.” Shapiro calls it “Perhaps the most extraordinary hardcore document I've ever heard . . . an hour-long series of masturbatory bleats, all thrash, completely airless.” He’s right: with these “records back to back to back to back to back to back with no breaks between songs . . . hardcore becomes pre-language, nothing but grunts, groans, chestbeating and brutal masculine energy.”

DJ Q-Bert, Demolition Pumpkin Squeeze Musik (Dirtstyle cassette, 1994/CD, 1999)

We end as we began, historicizing the DJ cut-up. Here’s Shapiro on Q-Bert, starting out with a then-au courant Francis Fukuyama reference:

If history is indeed over then the aseshetic of the mixtape . . . has become post-history's overarching narrative, and turntablists are its epic poets. The Odyssey of hip-hop mixtapes, and very likely the greatest of them all, is Q-Bert's utterly devastating 1994 mix . . . With some help from fellow Skratch Kiklz Shortkut and DJ Disk, Q-Bert calls them "pre-skool." Where Flash and Kool Herc created hip-hop out of the syncretic readymade of the breakbeat, Q-Bert colorizes and infests the break with his scratches and blocks of viral noise. With what would now be classed as rudimentary turntable skills, Flash's journey on the wheels of steel was more like a dip in the record crates. On Demolition Pumpkin Squeeze Musik the break is just the catalyst for Q-Bert's wildstyle jamming, which conjures a phonographic adventure through fantastic George Lucas-style mindscapes where the scratches sound like the shape-shifting video-game characters of Q-Bert's imagination. . . . The mix's high point arrives when Q-Bert stretches Bootsy Collins's bass line on James Brown's "Give It Up or Turnit A Loose" and then breaks it down along with the guitar riff into the Blackbyrds' "Rock Creek Park."

Q-Bert even saves the best for near-last, when a fizzy, horn-blown show-soul number boogaloos straight into a slowed-down electrobeat to set up a finale that comes complete with laugh-track, and then a banjo and horns. Hip-hop was anything and everything, and so was Shapiro’s writing. Farewell to a king.