WA005 - An Oral History of the Foxfire Coffee Lounge

Originally from 'City Pages,' a multivocal tribute to a pivotal Minneapolis all-ages venue

I had an abiding relationship with the venue celebrated below. When the Foxfire opened in 1998, I was twenty-three, drinking age but not a drinker, and it was a couple of blocks away from where I worked, so it was common for me to stop in there before or after work for coffee, to write and/or read. (Several City Pages pieces were drafted there.) And, needless to say, I went to the Foxfire to see shows—a lot of shows. It was immediately apparent that what was getting booked at the Foxfire was, in large part, not getting booked at First Avenue/7th Street Entry—my workplace at the time. Along with the raves I was hitting on weekends, this was a powerful trifecta. Even after I moved to Seattle in the summer of 1999, I was gutted when the Foxfire closed in 2000. It was as utopian a place as I’ve experienced.

Shortly after moving back to the Twin Cities—to St. Paul, rather than Minneapolis or its suburbs—I pitched then-City Pages music editor Jay Boller an oral history and to my gratitude he went for it. I turned it in and it got pushed back for a couple of months—newsier stuff beckoned, understandably. When it was ready to go, Jay had just moved up to EIC and my piece went onto the new music editor’s desk: Keith Harris, who had been a CP music writer and editor during the Foxfire’s run, and whose writing I quoted multiple times. When he returned the edits, he made sure to note that the really good quotes had come from Keith Harris. It was funny, but those quotes are good—they impart the place’s importance in no uncertain terms.

This is one of the pieces I’ve gotten the best feedback from—Sean McPherson of Heiruspecs and Jazz88.FM, then at The Current, was thrilled to see his band’s name in there. (I wish I’d thought to reach out to him, but this was our first meeting.) It’s quite a tale, and there’s a lot that will be familiar to anyone who’s ever wanted to make their own scene. There are a lot of new-ish Twin Cities venues afoot right now, many of which I still need to visit. (Racket published a guide—gift link—though some of it has likely changed in the fifteen months since it ran.) My priorities have shifted dramatically—the DJ events the Foxfire threw would be the primary reason for me to go now, not one among many—but the excitement of a scene finding itself was evident even at the time. There’s a lot of that going on right now, and it made me want to revisit the Foxfire’s history.

Today is my fiftieth birthday, so I’m republishing it, unlike other Waves Around posts, without a paywall.

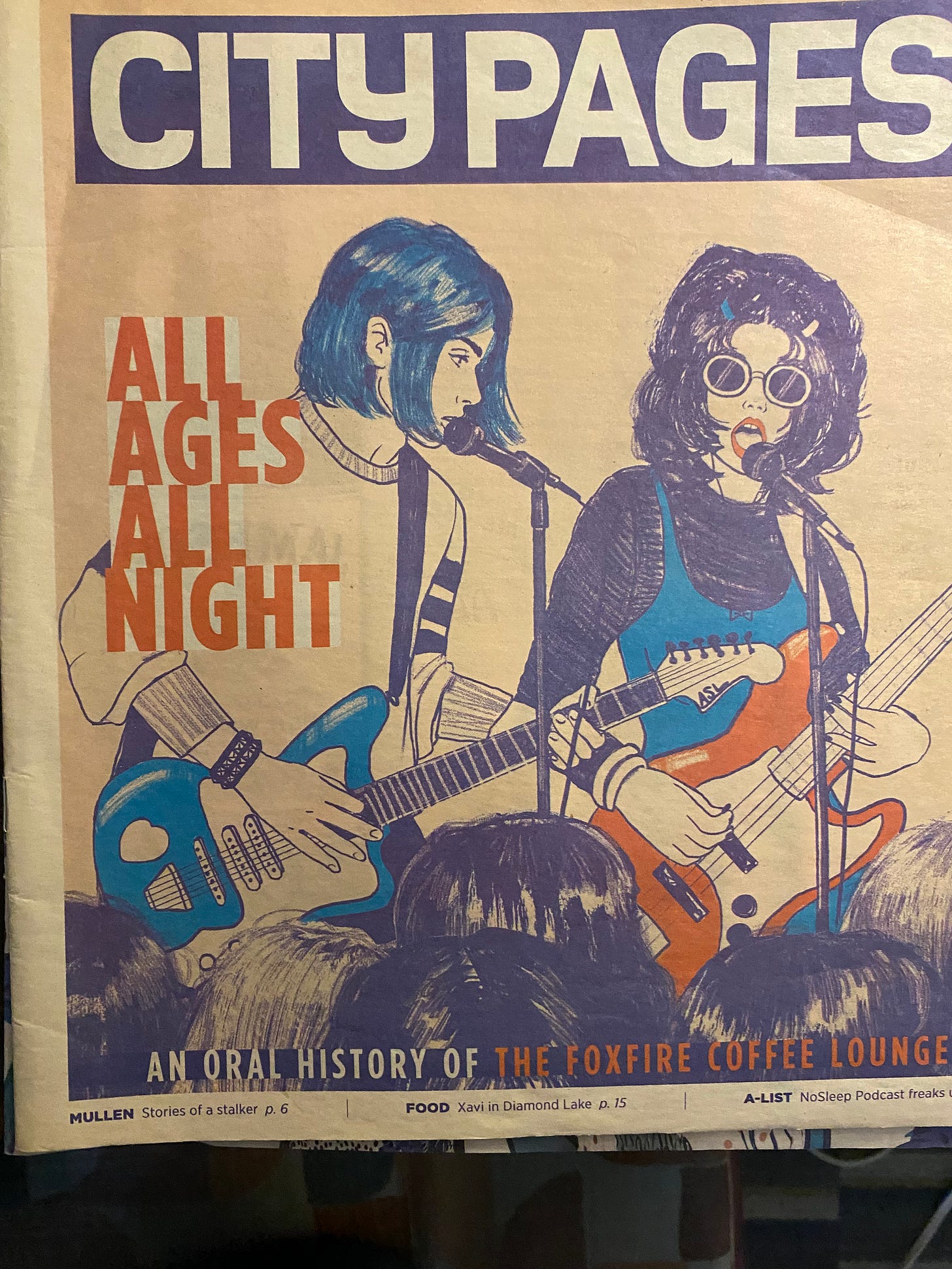

All Ages, All Night: An Oral History of the Foxfire Coffee Lounge [City Pages, February 22, 2017]

Elizabeth Larson had been thinking about a combo café and all-ages music space for a while. She committed to making it happen at “a Calvin Krime concert in Thompson’s Arcade,” City Pages’ Peter S. Scholtes reported in 1998. “She couldn’t see the band.” When Larson opened the Foxfire Coffee Lounge in downtown Minneapolis that summer, she made sure to build the stage high.

Larson had grown up in Lake Elmo and attended Seattle Pacific University, a Christian school. In the mid-nineties, she met Tom Rosenthal, a self-motivated singer-guitarist leading the pop-punk band Magnatone. “Larson scraped together her savings [and] drafted ‘a very expensive business plan’ to persuade loan officers,” wrote the Star Tribune. The well-connected Rosenthal booked the bands.

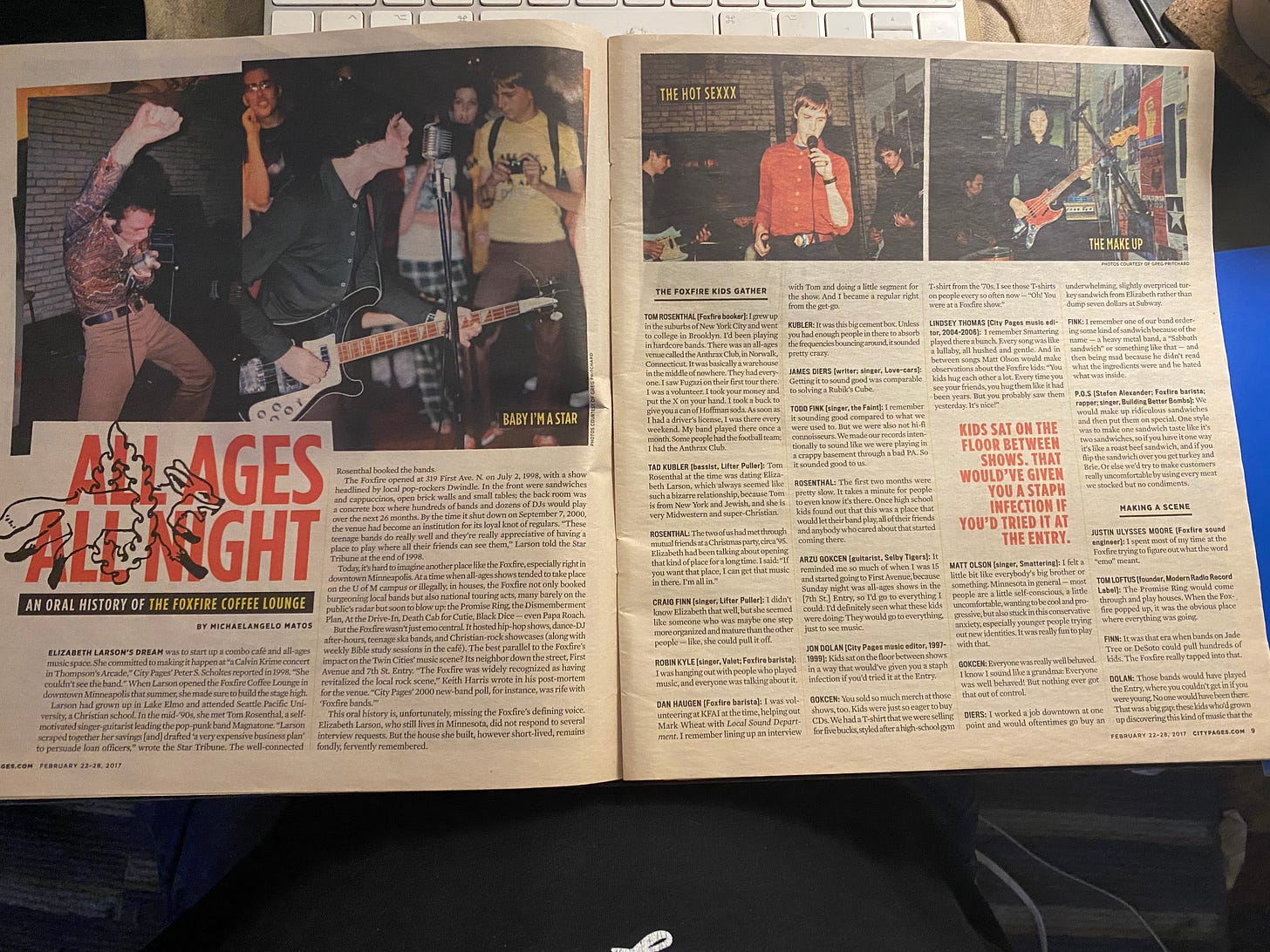

The Foxfire opened at 319 1st Avenue North on July 2, 1998, with a show headlined by local pop-rockers Dwindle. In the front were sandwiches and cappuccinos, open brick walls and small tables. The back room was a concrete box where hundreds of bands and dozens of DJs would play over the next 26 months. By the time it shut down on September 7, 2000, the venue had become an institution for its loyal knot of regulars. “These teenage bands do really well and they’re really appreciative of having a place to play where all their friends can see them,” Larson told the Star-Tribune at the end of 1998.

Today, it’s hard to imagine another place like the Foxfire, especially right in downtown Minneapolis. At a time when all-ages shows tended to take place on the U of M campus or illegally, in houses, the Foxfire not only booked burgeoning local bands but also national touring acts, many barely on the public’s radar but soon to blow up: The Promise Ring, the Dismemberment Plan, At the Drive-In, Death Cab for Cutie, Black Dice — even Papa Roach.

The Foxfire wasn’t just emo central. It hosted hip-hop shows, dance-DJ after-hours, teenage ska bands, and Christian-rock showcases (along with weekly bible-study sessions in the café). The best parallel to the Foxfire’s impact on the Twin Cities’ music scene? Its neighbor down the street, First Avenue and 7th Street Entry. “The Foxfire was widely recognized as having revitalized the local rock scene,” Keith Harris wrote in his post-mortem for the venue. “City Pages’ 2000 new-band poll, for instance, was rife with ‘Foxfire bands.’”

This oral history is, unfortunately, missing the Foxfire’s defining voice. Elizabeth Larson did not respond to several interview requests. But the house she built, however shortly lived, remains fondly, fervently remembered.

TOM ROSENTHAL [Foxfire booker]: I grew up in the suburbs of New York City and went to college in Brooklyn. I’d been playing in hardcore bands. There was an all-ages venue called the Anthrax Club, in Norwalk, Connecticut. It was basically a warehouse in the middle of nowhere. They had everyone. I saw Fugazi on their first tour there. I was a volunteer. I took your money and put the X on your hand. I took a buck to give you a can of Hoffman soda. As soon as I had a driver’s license, I was there every weekend. My band played there once a month. Some people had the football team; I had the Anthrax Club.

TAD KUBLER [bassist, Lifter Puller]: Tom Rosenthal at the time was dating Elizabeth Larson, which always seemed like such a bizarre relationship, because Tom is from New York and Jewish, and she is very Midwestern and super-Christian.

ROSENTHAL: The two of us had met through mutual friends at a Christmas party, circa ‘95. Elizabeth had been talking about opening that kind of place for a long time. I said: “If you want that place, I can get that music in there. I’m all in.”

CRAIG FINN [singer, Lifter Puller]: I didn’t know Elizabeth that well, but she seemed like someone who was maybe one step more organized and mature than the other people — like, she could pull it off.

ROBIN KYLE [singer, Valet; Foxfire barista]: I was hanging out with people who played music, and everyone was talking about it.

DAN HAUGEN [Foxfire barista]: I was volunteering at KFAI at the time, helping out Mark Wheat with Local Sound Department. Through the station, I had heard that Tom Rosenthal was going to be booking bands at a new all-age venue. I remember lining up an interview with Tom and doing a little segment for the show. And I became a regular right from the get-go. Half a year in, I started working part-time as a barista.

LINDSEY THOMAS [City Pages music editor, 2004-2006]: I moved to Minneapolis in 1999. The first show I went to was the Glory Record and Antarctica. I had a friend from the U who said, “I heard about this place that’s a coffee shop that also does shows. Wanna check it out?” I don’t remember anything about the show, but I knew right away, “This is a place I’m going to spend a lot of time.”

KUBLER: It was this big cement box. Unless you had enough people in there to absorb the frequencies bouncing around, it sounded pretty crazy.

JAMES DIERS [writer; singer, Love-cars]: Getting it to sound good was comparable to solving a Rubik’s Cube.

TODD FINK [singer, the Faint]: I remember it sounding good compared to what we were used to. But we were also not hi-fi connoisseurs. We made our records intentionally to sound like we were playing in a crappy basement through a bad PA. So it sounded good to us.

ROSENTHAL: The first two months were pretty slow. It takes a minute for people to even know it’s there. Once high school kids found out that this was a place that would let their band play, all of their friends and anybody who cared about that started coming there.

ARZU GOKCEN [guitarist, Selby Tigers]: It reminded me so much of when I was 15 and started going to First Avenue, because Sunday night was all-ages shows in the [7th Street] Entry, so I’d go to everything I could. I’d definitely seen what these kids were doing: They would go to everything, just to see music.

JON DOLAN [City Pages music editor, 1997-1999]: Kids sat on the floor between shows in a way that would’ve given you a staph infection if you’d tried it at the Entry.

GOKCEN: You sold so much merch at those shows, too. Kids were just so eager to buy CDs. We had a T-shirt that we were selling for five bucks, styled after a high-school gym T-shirt from the seventies. I see those T-shirts on people every so often now — “Oh! You were at a Foxfire show.”

THOMAS: I remember Smattering played there a bunch. Every song was like a lullaby, all hushed and gentle. And in between songs Matt Olson would make observations about the Foxfire kids: “You kids hug each other a lot. Every time you see your friends, you hug them like it had been years. But you probably saw them yesterday. It’s nice!”

MATT OLSON [singer, Smattering]: I felt a little bit like everybody’s big brother or something. Minnesota in general — most people are a little self-conscious, a little uncomfortable, wanting to be cool and progressive, but also stuck in this conservative anxiety, especially younger people trying out new identities. It was really fun to play with that.

GOKCEN: Everyone was really well behaved. I know I sound like a grandma: Everyone was well behaved! But nothing ever got that out of control.

DIERS: I worked a job downtown at one point and would oftentimes go buy an underwhelming, slightly overpriced turkey sandwich from Elizabeth rather than dump seven dollars at Subway.

FINK: I remember one of our band ordering some kind of sandwich because of the name — a heavy metal band, a “Sabbath sandwich” or something like that — and then being mad because he didn’t read what the ingredients were and he hated what was inside.

P.O.S. [Stefon Alexander; Foxfire barista; rapper; singer, Building Better Bombs]: We would make up ridiculous sandwiches and then put them on special. One style was to make one sandwich taste like it’s two sandwiches, so if you have it one way it’s like a roast beef sandwich, and if you flip the sandwich over you get turkey and Brie. Or else we’d try to make customers really uncomfortable by using every meat we stocked but no condiments.

JUSTIN ULYSSES MORSE [Foxfire sound engineer]: I spent most of my time at the Foxfire trying to figure out what the word “emo” meant.

TOM LOFTUS [founder, Modern Radio Record Label]: The Promise Ring would come through and play houses. The Whole covered that, and when the Foxfire popped up, it was the obvious place where everything was going.

FINN: It was that era when bands on Jade Tree or DeSoto could pull hundreds of kids. The Foxfire really tapped into that.

DOLAN: Those bands would have played the Entry, where you couldn’t get in if you were young. No one would have been there. That was a big gap: these kids who’d grown up discovering this kind of music that the older indie rock people didn’t know about, or didn’t have any interest in if they heard it, or were condescending even as it was really taking off.

THOMAS: Around that time, Make-Out Club was the big dating site for, lack of a better term, emo kids. I remember there was a time when I thought, “Maybe I should have a Make-Out Club account.” I went to check it out, and all of the Minneapolis people were just Foxfire kids.

TIGGER LUNNEY [former staff/booking agent, First Avenue]: I remember Tom showing me the big garage door opening to the back alley, saying, “Look how easy load-ins are going to be!” And I was like, “Look how easy it is to get wasted in this alleyway before a show!”

PATRICK COSTELLO [singer, Dillinger Four]: I joked for a long time that my favorite bar downtown was the stairwell in the alley to the stage at the Foxfire.

ROSENTHAL: Dillinger Four were problematic: All their fans thought it was cool as hell to smuggle in beers and drink them out in public. I get that you want to do that. I was that kid too, in a way. But you couldn’t do it there.

MORSE: Paddy was sitting on the toilet in the men’s room with the door open and all of his buddies and fans and friends were standing around while he was holding court — while he was dropping the deuce.

JEREMY ACKERMAN [singer, Walker Kong and the Dangermakers]: We did a show at the Foxfire where we played the last song in the men’s room, acoustically, with the majority of the people crammed into the restroom.

COSTELLO: I subsequently went to see Walker Kong and the Dangermakers several times because of that.

ACKERMAN: I was talking to Tom Rosenthal: “Oh, is there anything coming up with Lifter Puller?” And he’s like, “Dude, everybody wants to play with Lifter Puller.”

ROSENTHAL: Lifter Puller went across everything. Everybody got into them. At that time, they were about as big as you could get for a local band, especially for a band that had been around for less than five years.

AARON MADER [singer, the Plastic Constellations]: I’ve never seen a better show than those Lifter Puller shows at the Foxfire after The Entertainment and Arts EP came out. That sums up my high school experience.

ACKERMAN: If the Foxfire was CBGB’s, they were the Ramones.

COSTELLO: That stage was this condensed box; there was no way to walk away. Sometimes it made certain bands get a little more aggro and out there, and Lifter Puller was definitely one of them.

DIERS: The shitty sound did not matter because everyone was screaming the words to everything anyway.

KUBLER: Paul Grant, who was drafted by the Timberwolves, was coming to our shows. You can’t miss him, because the dude’s seven feet tall. After one of the Foxfire gigs he was like, “I love your band,” and rattled off all kinds of other bands. I was like, “This guy’s really into music.” He’s now my daughter Murphy’s godfather.

JAI HENRY [Foxfire barista]: The Plastic Constellations were the Superboy of rock bands there — incredibly tight, incredibly fun.

MADER: We were playing friends’ birthday parties and the school dance in junior high. Then the Foxfire opened and it was a total game-changer. That entire summer I think I went to every show there. I sent a handwritten letter to Tom and Elizabeth, thanking them. I remember the next week or two, seeing that letter taped up on the refrigerator, and being like, “Yes!”

ROSENTHAL: Aaron gave me their 7-inch, and the minute I spun it I knew I needed to meet these guys.

FINN: Aaron invited me to see the Plastic Constellations at Foxfire. Also on that bill was the Killer Bees, which was the Plastic Constellations dressing in bumblebee costumes and acting tough: “Yo! You ever get stung by a bee? That was us!” It was so high concept: they were so young to be understanding why this was so funny. That was the most amazing thing I saw at the Foxfire.

ROSENTHAL: Jimmy Eat World, although they were going for an all-ages scene, and definitely had devout followers in that, you could tell they were looking to get over, to become a pop act.

JUSTIN PIERRE [singer, Motion City Soundtrack; Cleveland Scene, January 24, 2005]: Jimmy Eat World would come through and they would put a local band on the bill. Because of [the Foxfire], we got to play in front of people who wouldn’t normally see us.

LOFTUS: Motion City Soundtrack was the first band that played on bills that were the baby brother of everyone else trying to get on anything. Now you’re like: How’s that even possible?

MADER: I remember seeing Heiruspecs’ CD release show and being like, “Oh shit, there’s a live hip-hop band that has horns. These kids are my age.”

LORI KYLE [Foxfire barista]: I remember the day Bill Clinton visited the Fine Line and all his people came into the Foxfire. All the Secret Service guys were up on the roof.

MORSE: There was also a Christian rock night they were doing, I think Wednesday nights. That seemed to always be the night of the week the tip jar got stolen.

STEVE PEDRO [Foxfire booker]: They weren’t there to preach — they were there to rock.

KUBLER: They’d have these totally chaotic punk rock shows, and then I would duck in there and they’d have a Christian Bible workshop in the back. At that time, it seemed like, “That’s crazy.” Where now I’d just be like, “Multipurpose room — sweet.”

ROBIN KYLE: We did a lot of techno nights. They’d go to four in the morning; some went even later than that. We sold a lot of Jones soda to [the ravers] — coffee, too, but mostly crazy-colored sodas.

ROSENTHAL: The Faint played the Foxfire at least half a dozen times.

FINK: When we first started playing proper clubs, I remember the Foxfire being the best one from those early tours. All the bands we met on the road on our level definitely knew of it, or had played there or were going to play there.

THOMAS: I remember the shows I was really upset I didn’t get to go to — particularly an At the Drive-In/Get Up Kids show, a double-header, two shows in one day, and it sold out immediately.

HENRY: It was a Halloween show. Those bands were huge as far as indie groups, so the energy of people being out in costume was pretty high.

HAUGEN: I remember the At the Drive-In frontman [Cedric Bixler] just running up the wall on the side of the stage.

HENRY: The drummer for the Get Up Kids was dressed up as a member of At the Drive In: an Afro wig, a dark denim vest. Also, one of them was Fred Durst.

MORSE: When you see Low at the 7th Street Entry, they want everyone to be quiet and not smoke and sit down, but you hear the noise from the Mainroom. When Low played at the Foxfire, everyone shut up. It was actually quiet.

LOFTUS: You look at those calendars: the Magnetic Fields, Low, Atmosphere, At the Drive-In, Papa Roach — I might not have wanted to see that. I remember thinking, “That’s a terrible name for a band.”

HENRY: With Papa Roach, we were all like, A: Who the hell are these guys; B: Why is it such a big deal? And C: Gross. We called it yo-metal, or bro-ternative. They’re trying to walk this line between emotional vulnerability and bad-ass-ness: “I’m sad, and I might beat you up.” You can’t have it both ways, bro.

LOFTUS: I always wondered, “How’s the Foxfire going to survive?” There’s no way it could have been sustainable. Pizza Luce was right down the street, and I remember people bringing Luce in. You can sell coffee, but how much coffee can one person drink in a night?

ROSENTHAL: We had plenty of very successful shows. But the profit margin for the Foxfire was not that much, even on a sold-out show.

MORSE: There were nights when the show sold out and they still lost money.

COSTELLO: I was working on the booking staff of the Triple Rock, and that’s when you realize: You book all-ages shows at a club? You’re doing it for the love of the game.

P.O.S.: There wasn’t enough of a day crowd to make the place stay open. What Liz said at the end was they needed to make an extra hundred bucks a day, and the place would have stayed open. It was cutting it that close.

ROSENTHAL: Elizabeth took me aside shortly before she announced it, to let me know first. It was definitely a bit abrupt. [She said] something to the effect of, “I have no choice but to do this now.”

KEITH HARRIS [CP, September 13, 2000]: The e-mail announcing that the Foxfire Coffee Lounge would be closing was sent out by one of its employees, Steven Pedro, at approximately 6:30 p.m. on Thursday, September 7. By 7:30, there were at least a half-dozen messages on my City Pages voicemail, and at least as many at home, some with questions, some passing along the information, but all tinged with shock.

P.O.S.: We found out that it was closing in the morning, and then spent all day lining up every band that we could imagine to come and play the farewell show.

THOMAS: I’d finished eating in the dining hall and went back to my dorm room and saw that it was the last night. I grabbed my earplugs and jumped on the bus, like: Drop everything, gotta go to the Foxfire.

ACKERMAN: Tom was totally bummed out. I think he took it harder than anybody. He was really invested in that club, and I think that was a hard, hard night for him.

DANNY SIGELMAN [writer]: The last night the Foxfire was open we were having a bachelor party for Jeremy [Ackerman]. I met up with everybody and said, “Let’s go down to the Foxfire — they’re closing tonight.”

THOMAS: Walker Kong and the Dangermakers retired the song “All Ages Club” that night. Jeremy said, “In honor of the Foxfire, we are never playing this song again.”

ROSENTHAL: Brokerdealer — [Finn had] started that in Minneapolis. I remember he was playing around with that when he first got to New York, before he put together the Hold Steady.

FINN: I’d been fooling around with [electronic producer] Mr. Projectile, recording demos. I was excited by something that didn’t require drums and bass rigs and a lot of equipment. Tom called, and we went down there and did it. That was one week before I moved to New York. I felt like, “If this isn’t going to be here, maybe this is a good time to be leaving.”

THOMAS: The whole night was about comforting each other with familiar things, and then Craig Finn got up and debuted his Brokerdealer music. Everybody was just like, “What the fuck was that?”

P.O.S.: It went all night, well past whatever bar time was there, and everybody was crying the whole time.

LORI KYLE: There was probably lots of alcohol that last night, too, snuck in.

KATE SILVER [Foxfire barista]: We hung out afterward till early in the morning, cleaning up and organizing things. I had to do the radio show [on Radio K] the next morning, and went directly there with my friend Nichole [Neuman]. We talked about it on the air. It really felt like a death.

ROSENTHAL: It was great, and it was sad. It was wonderful to have so many of the people who it truly meant something to be all there together and play all together in all this, but it didn’t hardly cover it. There was more to be said. You can’t get that in a day of performances, or in a couple days.

MADER: I don’t think I ever saw Elizabeth after that. She sort of disappeared.

ROSENTHAL: This is speculation — I would not presume to speak for her — but Elizabeth probably felt like she let a lot of people down, and she didn’t know how to face that. And I don’t blame her. Nobody thought about what it really took, business-wise, to make that thing happen or not.

THOMAS: I remember thinking, “I should have bought more sandwiches and Jones Soda.”

ACKERMAN: When it was gone, things sort of dispersed.

LOFTUS: It was a real scramble — a shuffling of the deck of the Twin Cities music community.

MADER: The Foxfire and the 1021 house both closed relatively [close together]. We literally had no place to play. We’d play a show at the Dinkytowner, and none of it really felt right. And our fan base immediately disappeared. Those kids who were coming in from Coon Rapids were not immediately searching for us after the Foxfire.

GOKCEN: It was so sad. That scene and everything it went through — I’m not dismissing the next couple things that tried to be venues there, but the spirit wasn’t the same. And they weren’t all-ages.

ACKERMAN: Twenty-six months? That’s hardly anything. But the impact seems big to me.

P.O.S.: Everybody that was touched by that place moved forward and really worked to smash out some real music and real albums. Everybody’s demo-sounding albums started sounding a little better.

LOFTUS: Years later, I was like, “Man — how did that place even exist? How did that one place host so much stuff at once, that were part of so many disparate, different subcultures that, frankly, never figured it out?”

ROSENTHAL: After the Foxfire was done, I decided to move back to New York. I went straight into graduate school. I remember playing at the Hexagon Bar with a cover band right before I left, and Elizabeth was there. I haven’t spoken to her since shortly after 9/11. I ran into her brother a couple years ago in Brooklyn at Union Hall. He said Elizabeth’s doing well. She’s married, has a kid. That’s about all I know.

I’d had this experience as a teenager of being a regular at all-ages shows, and being part of that scene. And I was so touched that I could give that to somebody else — and, apparently, lots of other people. That’s, to me, the biggest thing — I was able to help other people have that too.