BC010a – Q&A: Where DJ culture fits into the history of live music

The first of a two-part Q&A with historian Steve Waksman, author of the crucial new book 'Live Music in America.'

Following on from my consideration of DJ mixes in the canon, per The Guardian’s “Top 100 BBC Music Performances,” a couple weeks back, I figured this was a good time to share a longer version of a recent Q&A I did with Steve Waksman.

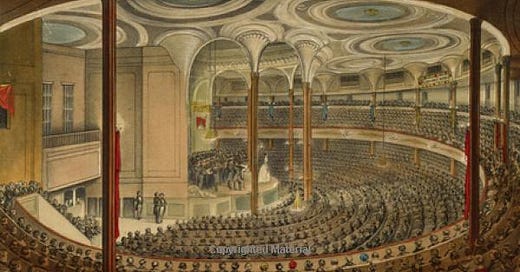

A music professor at Smith College, Waksman is the author of two previous books: Instruments of Desire: The Electric Guitar and the Shaping of Musical Experience (Harvard University Press, 1999) and This Ain’t the Summer of Love: Conflict and Crossover in Heavy Metal and Punk (University of California Press, 2009), that reflect his longtime adoration of hard rock and metal. But his new Live Music in America: From Jenny Lind to Beyoncé, just published by Oxford, is his most widescreen work to date—covering more than 170 years, from 1850, when the Swedish opera star Lind caused riots and inspired ticket scalping after P.T. Barnum brought her to the States, to Bey’s Homecoming show at Coachella in 2018.

Waksman rewrites the story of American music (popular and concert) while also wrestling with the animating idea of what, exactly, constitutes “liveness” in music, and how it has changed over the years. He’s been thinking about that question for fourteen years—and the more you think about it, the more essential it seems, especially post (or, really, mid) pandemic. But he’s also provided a nuts-and-bolts history of the art and business of presenting music to large (and sometimes smaller) audiences.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Beat Connection to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.