BC068 - Five Mixes: Old School, January-February 2024

From Italy in 1980 to Chicago’s late ’80s and London, mid-’90s

Daniele Baldelli, via Resident Advisor

I had already started earmarking these sets for inclusion in the year’s first edition when I realized that “Retro” was an idea that needed more follow-through—the sets should be new iterations of older material, deliberate look-backs or never-lefts. Actual old sets deserve their own post, and this is a particularly rich grouping. These sets follow in the order they were recently uploaded, not the order recorded. But chronologically, it’s quite a journey: from Italy in 1980 to Chicago in the late eighties to London in the mid-nineties. Like “techno” last time out, “Dance music” is an elastic term; so is “old school.”

Here are the first four sets as a SoundCloud playlist.

Farley “Jackmaster” Funk, 107.5 FM WCGI, Chicago, 1987 (Manny’z Tapez; uploaded January 15)

No surprise that Manny’z Tapez has taken some space in these parts—not only was its proprietor gracious enough to sit down on the phone and answer my questions, he keeps bringing the goods. He referred in that conversation to the Hot Mix 5—a rotating lineup of Saturday-night mix-show kings in Chicago during the eighties and nineties—as his “godfathers” as DJs. And it’s about time I said something specific about a couple of the sets I’ve illustrated both his Q&A and the DHP history it helped to shape. Chicago house is hitting in London and its triumph is manifest on this charming artifact: city-praising anthem, “Can You Feel It” avec MLK, “House Nation,” a whole world caught on a tape side.

DJ Trickster, Pt. 4 ‘Happy Stylee,’ Spring 1994 (Deep Inside the Oldskool; uploaded January 17)

This was posted by a SoundCloud account I’ve followed for a long time: Deep Inside the Oldskool, about which I wrote a bit earlier this year. (I was also reading their blog.) They fueled not only my book but my Wire Primer on pirate radio DJ sets (April 2018). They tag this one, hello, as #happyhardcore. Is it ever—but there are key differences between this and, say, the Andy Pav 1994-95 mix covered here, retrospect not the least of them. Let’s start with the speed of the thing—these records are already pretty fast and are being spun at +8, rendering them bright and blithering, literally being fast-forwarded as they’re played. It’s hardly perfect; records go out of phase here and there. But the quiet moments deliver an even deeper tingle at this speed, and the pianos, of course, sound atomic.

Krome & Time, Joint Forces, 28th October 1993 (Deep Inside the Oldskool; uploaded January 31)

Hackney’s DJ Krome and Mr. Time, to give them their full sobriquets, were a pair of early UK hardcore stalwarts who made the transition into production early on. Their “This Sound Is for the Underground” was one of 1992’s defining UK hardcore anthems; their 1993 “The Slammer” is one of my favorite recordings of the era. (Both are on Suburban Base.) Krome & Time’s early work, even more than their peers’, played straight into the happy hardcore discussed above, but they also exemplified the commonalities between the increasingly minimalist and serious drum & bass wing that would overtake jungle by mid-decade, with happycore receiving the bulk of the pianos and divas in the divorce. Two years on from their September 1991 set from the Suburban Base showcase at Madisons, Bournemouth—as I wrote for Mixmag, “dizzying in every way imaginable: London hardcore caught during the giddy early part of its mutation from house to jungle”—this mixtape is the honeymoon period burning bright but fraying at the edges.

Andre Hatchett, Live @ AKA, Chicago, 1985 (Manny’z Tapez; uploaded February 16)

One of the things that made DHP’s uploaded tapes so revelatory is that you could still catch the magic even through sometimes heavy aural grime. One of the things that makes Manny’z Tapez so valuable is that he works to maximize his uploads’ sound quality, and that’s particularly evident with this one. It’s a rarity—on the SC page, Manny asks anyone reading for access to the missing Side B, if it exists—and it’s stunning to encounter, its hard-angled cuts and deliberate fluctuations of volume as bracing as when recorded.

Andre Hatchett was part of the Chosen Few, a DJ crew from Chicago’s South Side, now known for their annual picnic but in the early eighties a fearsome group of promoter-producers. Alan King explained their genesis to 5 Magazine in January 2006:

In the late '70s leading into the '80s, while I was gaining a reputation as a DJ, the other popular DJs on the south side were Wayne Williams (now VP of A&R for Jive Records in New York), Jesse Saunders and Tony Hatchett (older brother of Andre Hatchett). Eventually, we all came together as one crew and basically started playing most of the hot parties on the south side at various nightspots, including the Loft, the Tree of Life, First Impressions, Sauer's and South Commons. Wayne dubbed the crew the "Chosen Few" and the rest, I guess, is some degree of history.

In 1980, the Chosen Few were resident DJs at the Loft (located at 1416 South Michigan Avenue), which was a very important venue in the birth and development of what would become known as "House Music." At the Loft, we were basically replicating, as best we could, what Frankie Knuckles was then doing for a slightly older, largely gay crowd at the Warehouse, for a crowd that consisted of mostly straight teenagers who had never experienced anything like it.

Parties at the Loft lasted from 10:00 p.m. or so until 8:00-9:00 a.m. the next morning, and were very intense. A lot of future House music legends received their "baptism" attending the Loft, including Steve "Silk" Hurley and Chip E. The Loft was also where Andre Hatchett made his DJ debut at a party promoted by Craig Loftis' promotion group, Vertigo.

You can hear, immediately and throughout, just what gave Andre Hatchett and his fellows the audacity to dub themselves with that group name. It’s not the rarity of what Hatchett is playing—even a disco novice could ID some of these songs—but the acuity and charging manner with which he serves them up. This set gathers momentum throughout—the tempos don’t accelerate noticeably, but the selections stay at a feverish pitch. To use another old-fashioned term, it romps.

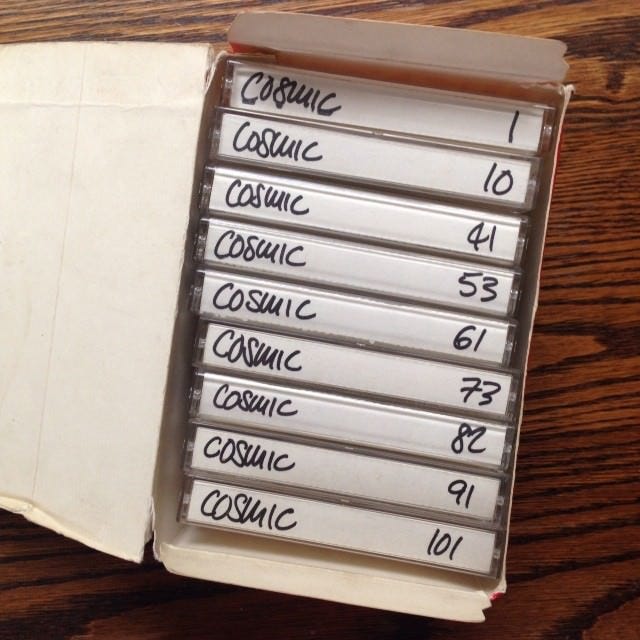

DJ Daniele Baldelli, Cosmic 01 (1980) (Internet Archive; uploaded February 20)

That name again: DJ Daniele Baldelli. Once upon a time, particularly in 1980, if you were a DJ playing a club, you put “DJ” in front of your name. It was mandatory. That tells us about what era we’re in before we even hit play. Immediately, the headphones in your mind’s eye take on a brontosaur quality, and so do the grooves, particularly since I haven’t listened to much early Baldelli and was quite enticed by his Rinse set for Horse Meat Disco in August 2018. More of a flavor for the type of music Baldelli helped can be found in Peter Shapiro’s “Dancing in Outer Space,” his glorious overview of cosmic disco published in The Wire’s August 2010 issue. Shapiro wrote:

[I]n the right hands, disco yearned for the cosmic sublime as surely as any communal Ya Ho Wha 13 or Acid Mothers Temple jam. . . . disco got truly cosmic when it ditched its feather boa for silver Mylar bodysuits and tried to soar to the stars. . . . disco’s embrace of interstellar space marked both pop music’s first true futurism movement (before you yell at me about Sun Ra or ‘Telstar’ or ‘Flying Saucers Rock & Roll’ or Floyd/Hawkwind, please read that clause again) and a sideways retreat to disco’s eclectic roots after its spectacular mainstream supernova flameout.

He further describes cosmic disco as a style where “where continental Europeans unequivocally call the shots,” the home of “both quickie cash-in records and the most artful, dazzling, psychedelic DJ sets you are ever likely to hear: weedy, buttoned-up computer nerds and charismatic, hirsute astral travelers; Cosey Fanni Tutti and Fela Kuti.” Shapiro gives Baldelli the spotlight for a good chunk of the piece, bestowing upon him a generous sobriquet, even with the requisite distancing clause up top: “It wouldn’t be much of a stretch to declare Daniele Baldelli the greatest DJ ever.”

That’s a lot of preambles for one 90-minute set, but I’d imagine a listener could feel the weight of history on this mix even without it. The eclecticism Shapiro spotlights is important, and he quotes Baldelli on it: “From 1980 to ’84, something new started in me. I started listening to every kind of music.” Later, the DJ adds: “I am Italian, so I don’t understand the words anyway. The voice this way is simply music.” This applies to both the breadth of his stylistic affinities and his penchant for playing records at way-wrong speeds, which was part of what gives Baldelli’s sets their heavy vibe.

By default, the first edition of a mix by any putative “greatest DJ ever” is of historical significance. It’s not as if there’s been an shortage of Baldelli sets online, though. The Mixcloud account from Italy’s Old School L’Inizio di Tutto crawls with mixes from Baldelli and cosmic disco colleagues like Beppe Loda, among many others, and it’s hardly alone. The set under review, in fact, has been on YouTube for more than a dozen years, where Baldelli shares the credit with TCB. But seeing the set spotlighted by RA’s Mix of the Day after its appearance on the Internet Archive made it a good reason to look back. And in fact, I have listened to his before, at that very YouTube link, years ago—likely right after reading Shapiro’s piece and starting at the beginning. I didn’t pick it up from there—that may be a project down the line, maybe. (Your votes count! See BC064.)

The YouTube link also includes a near-complete tracklist for Cosmic 01, and it’s worth a gander by itself. (One song is missing, the ninth selection on the first half, between “Do a Dance for Love” and “Kind of Life.”) There is no wall here between R&B (Cameo, Brenda Harris, Kool & the Gang) and prog-rock (it opens with “Madrigal Meridian”), not an unknown taste confluence, but geared here toward the Euro grandeur Shapiro identifies above. It’s a confident and audacious start to the series (not a start to his career—Baldelli had been playing for years by then), but it’s hardly the whole enchilada. (If you are used to absolutely perfect mixing, moments of this may unsettle you. Things were different then, that’s all.) The best stretch occurs near the final quarter, following freakin’ Edgar Winter: “Go for It” > “Willie Rap” > “Get Me to the Disco” > “Spoonin’ Rap” is a glorious sequence. It makes me want to grab my roller skates, and I can’t roller skate.