BC121 - Five Mixes: Unknown DJs, 1978-2000

Who was that? And what did they sound like?

via Spreadshirt

Music lovers like to say they’re about the music—ergo, not about the hype or personality-driven narrative thrust accompanying the music. I do this a lot myself. That’s part of my attraction to DJ sets—getting to hear music in sometimes unexpected but often surprisingly congruent ways, and in ways where that hype or narrative means less than how the recording communicates in another setting. And yet, DJ sets are often not anonymous. A DJ’s signature—the consistencies of material, approach, and timing that help inform us of who’s playing the records as well as who made them—can be easy to exaggerate. I’ve done it before and I’ll do it again. But that’s part of the enticement of this type of engagement—the interpretive power of a good DJ can transform the music in ways its makers and fans might not have considered. In the case of digital DJs who cut up and realign existing tracks on the fly so that they sound like something else (and also themselves), that sort of hands-on action is part of the medium’s stylistic bloodstream.

However, anyone who dotes on early dance-music sets is going to see a lot of mixes from anonymous and/or unknown DJs over time—an unidentified radio mixer, an unmarked reel, a much-dubbed and/or passed around live tape, a stray MP3 that didn’t get tagged at all, who knows what else. These can have an allure of their own—or at least illustrate their period just as music, like these five do. No playlist this time around; aptly, the sources are too far flung.

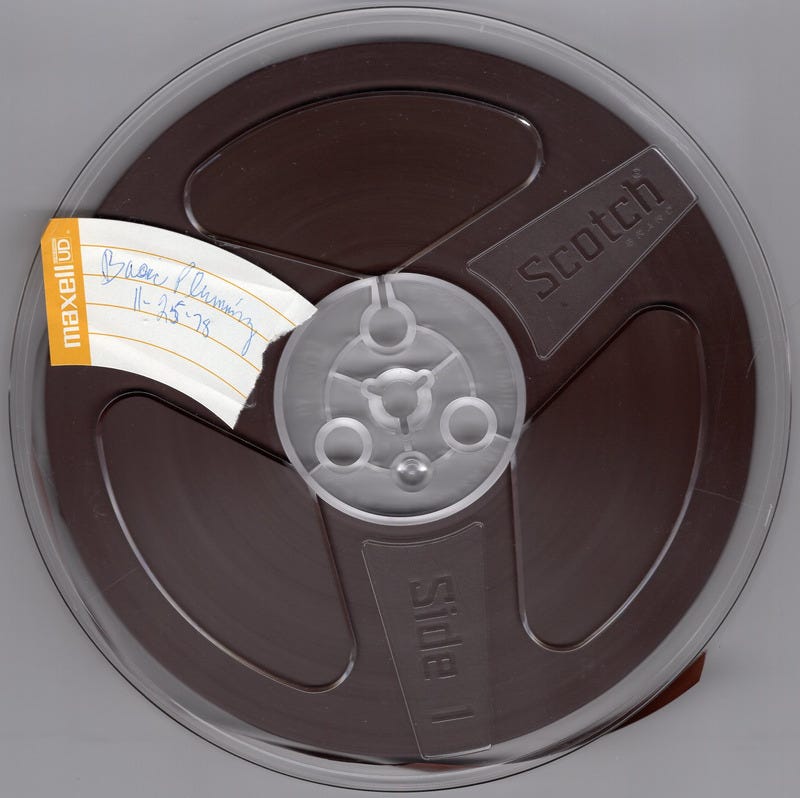

DJ ?, Basic Plumbing 11-25-78 (Jim Hopkins Remaster) (SF Disco Preservation Society; uploaded November 11, 2023)

I could have (and could still) do an entire anonymous-DJ Five Mixes from the SFDPS archives alone, just as I could from the Pine Walk below. This was the most recent from an unidentified jock in their archive—but I picked it for the title, and for this brief, tantalizing description: “From the Rod Roderick reel-to-reel mixtape archives. This sounds like it could be an old bathhouse tape.” Not even that quite prepared me for three hours that seem to never stop unfolding. Sure, there’s lots of funk and disco, proper—but there’s also abundant amounts of jazz fusion, of early synth-scapes, of acid-edged rock. Axemanship plays a heavy role on these selections, full of unapologetic sweat and swarthiness. From “Sheep” into “The Boy’s Doin’ It” into Mort Garson, to pick but one triad, is some kind of mission statement. Is the DJ named Basic Plumbing?

n/a, Hot Night, December 1979 (The Pine Walk Collection; uploaded 2022)

Yes, the same one John Darnielle pointed to in his Five Mixes interview (cf. BC084). A DJ’s anonymity can bite when you hear some notable bit of sleight-of-hand going on during a set. This offers a good example @ 8:20, when our selector slides quite suddenly away from the second of a Dan Hartman twofer into “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough.” (A similar what’s-that? moment occurs during some of the fader-cuts in the Haçienda mix below.) It’s not a singular move or anything, but it’s good, and I like to credit people who are good.

It’s also conspicuous here, because most of the other blends or cuts are near-invisible. The exceptions mainly get the dirty work done with swift authority, such as “Working My Way Back to You” giving way to “Baby Come Back” (@ 47:25), though this jock also gets off a daring ten-second ride between “Do Me Good” and “Evita Medley—Side B” (@ 1:02:00) where you can hear them juggle the speed of each one in turn, cool as a cucumber. It helps, too, that the records were becoming ever more automated. The evenly-laid train-track of the beat, along with the expanded palette of the twelve-inch single, facilitated easier mixing.

Automation is the great bugaboo of the era in rock-critical terms—“inhuman,” et al.; Walter Hughes addressed it more than thirty years ago. But it’s noticeable on this set for the same reason the DJing isn’t—you can still hear, meaning detect, the occasional human drummer on board, even if they’re human metronomes like John Robinson (“Don’t Stop”) or Jim Capaldi (“Shoe Shine [Disco Mix],” @ 1:26:55). The drummer gamely stomping his boot to a click track on “Baby Come Back” gives the tune some oomph, but it’s an obscurity for good reason, however lively it sounds in this setting.

But it’s the setting that matters here—ninety minutes that happens to capture many of the major currents in the disco moment at the end of 1979, which also looked like the potential end of the line for disco and the record biz in general. That December was the same month that Chic’s Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards told Billboard they weren’t going to make disco anymore. They did, of course, but everyone tacitly agreed to call it something else. Sometimes they even called it “rock.” By comparison, nobody then or now would have called this anonymously spun tape “rock,” or anything like it. Have I mentioned “Evita Medley—Side B”?

Hacienda exterior, 2001; via Blog51

Unknown DJ, 1990 Haçienda Spring (ish) (Blog51: The Hacienda; uploaded January 16, 2013)

Back in 2016, I wrote a piece for Pitchfork that’s a progenitor of this newsletter, choosing five (really seven) DJ mixes from Manchester’s Haçienda, the club founded by Tony Wilson, funded by New Order, foundational to the UK acid-house explosion, and folded by 1997. That piece’s primary source was the still-up Blog51: The Hacienda, which is full of mixes from the club’s lifetime—such as this two-parter from the very pit of “Madchester” frenzy by some DJ or other: “Odds on it is [Graeme] Park and [Mike] Pickering, or it could be Jon Da Silva, or [Laurent] Garnier . . . oh, you get the picture,” writes Blog51 proprietor Andrew McKim. And guess what? The Mediafire links on the blog post still work!

As you’d hope, it’s a lively, if lo-fi, glimpse at an era that was storied from its inception. To be specific, this isn’t a Madchester set at all—none of the baggy guitar stuff associated with that term. It’s increasingly internationalized house music with hip-house (not hip-hop) peering in. Lots of Morse-code keyboard riffs of all varieties: graceful post-gospel piano, itchy plastic synth, noisome buzz. The chunky breakbeats that strew it were absolutely standard by then. “The Power” must have still been “underground” at this point, LOL. It's all so wiggly.

Unknown DJ, A Virtual Reality Production—Early 1995 (Deep Inside the Oldskool; uploaded October 27, 2017)

Here’s an example of a subgenre unique to the realm—a set commonly mis-credited to a big scene figure, but that is otherwise unaccountable. In the case of this drum & bass “bootleg tape,” as JJ of Deep Inside the Oldskool notes: “It says Randall on the cover, but it's another DJ on the tape” (cf. BC088). With all due respect to whoever made this tape, it’s not even close to Randall in terms of technique or pacing-and-building. It’s also not much like Randall because it’s not a live tape—most of his were because he played out so much—but a home recording that, impressively, finishes Side A with a record timed to end precisely at its close. By early 1995, sizably engineered drum samples being filleted over sparser but deeper sub-bass and the wispy ghosts of the breaks’ original sources dominated the music, and the set reflects it entertainingly. But it’s also—you knew it was coming—a little anonymous.

n/a, Random tape—Garage pirate stations (Pure Magic 90.2, Taste 92.5 and Delight 103) (London; c. 2000)

This one comes to us courtesy of . . . well, in part, me. I didn’t record the tape, and wasn’t the DJ, and didn’t make any of the tracks (just to clear things up, ahem), but I did find and download it from a mixes-sharing forum thread I’d found after Googling something else. The actual file name I gave it—the info you see above, copied and pasted from that forum thread that gave me a working link to this audio—does not match its metadata, so your mileage very well may vary. So even if the listening gives me relevant info, I came to it without that—and indeed I may not have come to it if it were not for that very anonymity.

In any event, this is one of the earliest sets I downloaded for the project-in-progress for The Underground Is Massive, and it’s also one of the first sets I put on Mixcloud with the idea of making it part of my Wire Primer on pirate radio DJ sets, from the April 2018 issue. It didn’t make it onto that list, nor into the book’s Mixography—not because it’s bad but because it wasn’t definitive enough to fit with either. For example, in the Primer, I went with two Blu & Maddness shows from 1995 and 1996, not to mention EZ’s all-Todd Edwards set from ’98, so we’re square, trust. And UKG wasn’t big enough in the States to warrant much notice till the last chapter, which catches the first U.S. bubbling of Disclosure, who are in the Chapter 18 Mixography with their Fact Mix (2011), along with EZ’s FabricLive 71 (2013), and on the Mixmag 2010s list we went with EZ’s also equally estimable Boiler Room from 2012.

Those just named have, in their different ways, a classic kind of shapeliness. This one is less definitive—it’s forty-five minutes grabbed on the run that gathers momentum anyway. The first station is shuffled off to Buffalo in fairly short order—song starts to drag, pause, next. The MC of station two, Taste 92.5, ID’s himself as Flava D—no relation, it seems apparent, to the current Flava D—and the DJ as Kasha, if that isn’t misspelled. Even if so, the tracks jump—even “Follow Me,” whose hats and bass line, when sped up to properly quick UKG tempo, really pop, and when that’s finished, things really heat up: the Gurley “Red Alert” re-lick, K-Ci & JoJo taking us out on a helium balloon ride. When the tape runs out, it’s like walking through a wall.